Engineering Your Career (Part 2): Licensing

This article is part of the Professional Advancement Series: Engineering Your Career

This article appeared in Machine Design and has been published here with permission.

An important step in an engineer’s career is obtaining a professional engineering license. The license, and the PE after your name, sets you apart from others and tells the public you have the education, experience and qualifications to solve their engineering problems. To understand the value of a PE license in relation to an individual career, here’s a look at the history of licensure in the U.S., the value of the PE and challenges to the current licensing system.

History

It is common to see professions and occupations regulated through a licensure system, but it wasn’t always so. As late as the early 1900s, anyone could practice engineering, and this put public safety at risk. Engineer David Steinman recognized the risk to the public and was concerned about the situation, so he began advocating for a licensing system for the competent and ethical practice of engineering.

In 1935, Steinman said: “The technical problems of civil, mechanical, electrical, mining, and chemical engineers are divergent; but the professional problems are alike. The technical societies, for the best fulfillment of their essential purpose, are divided on lines of differentiation of technical branches or specialties. This division into separate organizations, with diverse traditions and viewpoints, prevents effective united effort for the interests of the profession. A single national professional society with solidarity of purpose and concentration of strength,is needed to effectively provide for the professional interests of the engineering profession.”

As late as the early 1900s, anyone could practice engineering, and this put public safety at risk.

Professional licensure is a responsibility delegated to each state by the U.S. Constitution, but Steinman saw the need for an organized effort to establish professional engineering licensure across all the states. To reach this monumental goal, Steinman crafted a framework for creating the National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE). It was then founded in 1934 with the mission of advocating for establishing PE licensing in all the states to protect engineers (and the public) from unqualified practitioners, build recognition for the profession, and stand against unethical practices and inadequate compensation.

In 1907, Wyoming become the first state to adopt a licensing system. By 1959, when Alaska and Hawaii were granted statehood, all 50 states had licensing systems.

In 1920, as state licensing boards recognized the need for a national council to make rules and laws more uniform and promote mobility of engineering licenses, the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying (NCEES) was created. Today, the council’s members are comprised of the 69 engineering and surveying boards from all U.S. states and territories. Through NCEES, states and territories have worked to provide uniform model laws and rules, promote professional ethics among engineers and shape the future of professional licensing. For more than 100 years, public health, safety and welfare have been improved by the protections provided through engineering licensure laws.

The Value of the PE

Through rigorous standards for education, experience and examination, the PE license protects the public health and safety from unqualified practitioners. But what does it mean to individual engineers? Simply put, it means options and money.

Although a PE license is not required for all engineering jobs due to industry and government exemptions, it is required for many. In many states a person must hold a PE license to own an engineering firm, provide consulting services and to call themselves an engineer. If someone chooses not to obtain a PE license by earning a degree from an approved college or university, passing the necessary exams upon graduation, and working under a licensed professional engineer for the prescribed time, they limit their options for employment and most likely reduce their earning potential.

Additionally, the work of engineers affects not just the individual buyer; in many cases it also affects the public at large.

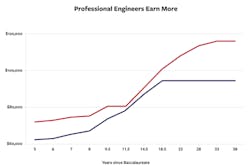

In the rapidly changing world, young professionals and students should keep all options open and available. Obtaining a PE license does just that. Data clearly shows that engineers with PE licenses earn more money than those who don’t.

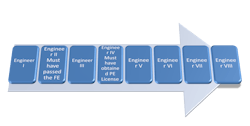

For example, at my firm, the career ladder for engineers starts at an Engineer 1 (a new graduate) and progresses up to an Engineer 8, with pay increasing as a person moves up the ladder. To move to an Engineer 2 position, a person must pass a Fundamentals of Engineering (FE) exam, which is also a PE a requirement in earning a PE license. To advance to Engineer 4, they must get a PE license.

An Engineer 4 makes significantly more money than an Engineer 1 or 2. More money and more responsibility equate to challenging and rewarding opportunities and job satisfaction.

Pressures for Change

If a PE license is so valuable and necessary, why are there so many exemptions? Why are state license boards under continual fire to abolish licensure? Perhaps a change is needed so that the license’s value, and the protection it affords to the public, remains constant in our ever-changing world.

The debate over the government’s role in regulating occupations and professions has recently come to the forefront. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics, occupational licensing directly affects nearly 30% of U.S. workers, including barbers, cosmetologists, florists, interior designers, manicurists and a long list of others. Although the work of professional engineers—like that of doctors, registered architects, and attorneys—clearly affects public health, safety, and welfare, it is not uncommon for state legislatures to categorize highly educated and trained PEs with barbers and cosmetologists in the debate over eliminating occupational licenses.

For example, 2015 model legislation championed by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), an association of state lawmakers that supports private-sector interests, led to a recommendation that would have eliminated PE licenses in Indiana.

As the result of extensive advocacy efforts by the Indiana Society of Professional Engineers and NSPE, the Indiana Job Creation Commission, inspired by ALEC’s model law, rescinded its troubling recommendation to eliminate licensure of professional engineers. However, nearly identical versions of this legislation were quickly introduced in several other states, and variations of that legislation persist today across the country.

Although ALEC’s legislation does not specifically target PEs, it opposes occupational licensure in general. This broad attack undermines PE’s value and unintentionally affects engineering licensure. Clearly this is an attempt to muddy the difference between occupations and professions. Much work remains to be done in educating the public and especially legislators on what licensed professional engineers do and why they are critical to the continued health, safety, and welfare of the public.

In dissecting this issue, it is important to first understand the form these challenges take when introduced to state legislators. The repeated legislative threats to our licensure system come in various forms but can be grouped into four categories:

- Consumer choice

- Least restrictive

- Right to earn a living

- Universal licensing

Consumer-choice legislation is the most dangerous of the licensing threats because it seeks to let anyone practice any profession, regardless of whether they are licensed. NSPE refers to this as “buyer beware” because it places the onus entirely on consumers to determine if someone is qualified to practice engineering. This is problematic as the public generally doesn’t understand engineering and how to select qualified professionals. Additionally, the work of engineers affects not just the individual buyer; in many cases it also affects the public at large. For instance, do consumers have a say in selecting the engineers who will design the bridge they will drive over or the trains and planes they will ride in?

Legislation commonly referred to as “least restrictive” is also a significant threat because it assumes market competition will protect the public. This assumption removes preventative measures in licensing regulations intended to protect the public. The only recourse for consumers comes after something has gone wrong. Even then, consumers are limited to legal actions.

Right to earn a living legislation comes primarily from the American Legislative Exchange Council. ALEC has developed model legislation that requires a state’s licensing boards to review all licensing regulations. Typically, this type of legislation uses the “least restrictive” approach described above.

The fourth type of legislative threat comes in the form of universal licensing. These bills are not a threat in and of themselves, but they occasionally include language that lowers the standards required for licensing. For example, they may let applicants substitute work experience for education or may not require that the applicant’s original licensing state have the same education and experience requirements. Sometimes this legislation seeks to prevent a state from requiring a state-specific exam, which is problematic for states such as Alaska, Florida, and California that require additional technical knowledge to address local issues, such as seismic activity.

Professional engineer should use their influence and prestige to mentor others and help develop future engineering leaders.

Emerging Fields

There is no doubt that new and better technologies will continue to be developed and implemented, often at breakneck speeds. And while new technologies aren’t inherently bad, they should be developed so that the public health, safety, and welfare are protected. Ensuring the ethical development and testing of new technologies, such as autonomous vehicles, and including a professional engineer in developing and deploying those technologies can help. To date, much of the discussion on emerging technologies has been about their capabilities and perceived public benefits, but many questions remain unanswered, especially around ethics:

- How will these technologies affect our behavior and interactions?

- How can we guard against mistakes?

- How do we eliminate bias in these technologies?

- How do we keep technology safe from safe from terrorists or countries with ill intent?

- How do we protect against unintended consequences?

Answers to these questions and many others must be found so the considerable risks can be mitigated, and society can reap the full benefits of emerging technologies. The public’s interests are best served when licensed professional engineers oversee the design, development, and deployment of emerging technologies to address uncertainties. Engineers as a profession and individual professionals should contribute to these emerging fields and use their knowledge and experience for the greater good.

Professional engineers should use their influence and prestige to mentor others and help develop future engineering leaders. Engineers who have not obtained their PE licenses should learn more about the process and the opportunities a license provides. And engineers should help elected officials and decision-makers understand the value of engineering and its impact on people’s daily lives.

Read more from the Professional Advancement Series: Engineering Your Career