This article is in the Electronic History topic within our Series Library

Besides a safe, loving home, enough to eat, and a good education, I wish for all of the world’s children an Uncle Martin. While they may go by another name, may not be any kind of blood relation, and may not even be a guy, every kid needs an adult like my Uncle Martin to listen to them, believe in them, and help open their eyes to life’s adventures. Now that I’ve somehow managed to make it to my own adulthood, one of my life’s goals is to become at least one child’s Uncle Martin.

To be precise, Uncle Martin was my great uncle—a treasure inherited from my mother’s side of the family. Although he did not invent the word “eccentric,” I'm pretty sure he was on the committee that defined its functional specifications and, that his dear wife, Esther, was the recording secretary for the committee.

During his working life, Martin was, in no particular order, an inventor, an auto parts counterman (in the days of Ford's Model A), a repair shop foreman, a cemetery plot salesman, an unlicensed commercial biplane pilot, a watchmaker, and always, a teacher.

Although much of his late adulthood was spent teaching drafting, wood shop, aviation technology, and jet engine repair to teenagers at a Vo-Tech in inner city Brooklyn, N.Y., a great deal of the important things that he and Esther taught were by the example of their own lives. Anybody lucky enough to spend time around them got to experience what living a life of kindness, commitment, respect, and a deep curiosity about almost everything felt like.

I remember being very young, perhaps nine or ten, sitting with Martin at the dining room table in his row home on President Street, and peppering him with questions about flying and airplanes. My fascination with airplanes and rockets was not new. It was a persistent itch that had appeared well before I was five and demanded increasingly frequent scratching as my curiosity and ability to understand things grew. Since he had actually built and flown airplanes, Martin was the frequent target of my naïve and unfocused questions about the field.

The table we sat at was where our family often shared holiday meals. It was also where I spent many happy hours at Martin’s side as he repaired radios, toasters, vacuum cleaners, and other pieces of equipment he’d rescued from the neighborhood trash. Perhaps it’s a trick of a fading memory, but I clearly remember a smile coming to his face as he said in his cigarette-roughened voice, “So you like airplanes? C’mon, we’re going downstairs. I've got something there I think you’ll like.”

Wonders in the Basement

A trip to my Uncle Martin’s basement was in itself cause for excitement. Exploring the vast, musty space was an adventure that rivaled the thrill archeologists must have felt when they first fell upon the wonders of King Tutankhamen’s tomb.

Descending the creaky stairs ahead of me, he clicked on a few bare bulbs and threaded his way past a tool-cluttered workbench toward the rows of heavily laden shelves that lined the deep recesses of his inner sanctum. I followed him past a shelf full of washing-machine motors, another containing electrical hardware, and others stacked with bins of springs, screws, watch parts, and other assorted hardware, all neatly filed for future use.

Martin clicked on another light and carefully moved aside a carbon arc light he’d salvaged from a defunct theater, and then rearranged a piece of dental apparatus he promised to repair for a friend several years earlier.

Much like the movement of tectonic plates, Martin’s repair projects operated on geological time. Items entering his repair queue would be subducted into the basement's slowly shifting mantle of detritus where it would remain for months, years, or perhaps even decades – until emerging whole once again, and often working better than new.

The “Box”

Finally, we came to the back corner of the room and Martin poked around until he found a cardboard box, apparently about half-filled with papers. A wave of disappointment came over me—I’d been hoping to find an old model airplane or perhaps even some piece of a real airplane, and was not too sure what a box full of papers had to do with flying. Before I could say anything, we took our leave of the basement and returned to the dining room table to inspect the contents of the box.

“You know I used to do some flying” said Martin, “and I also got to work on some pretty interesting airplanes.” I nodded gravely, trying to figure out where he was going with this. “Well,” he said triumphantly, “I packed away a buncha souvenirs away in case I had a curious young nephew like you come along.”

He passed the box over to me and I peered in. The first thing I saw staring up at me from the dusty interior was a pamphlet, showing a strange-looking plane, with a pointy nose, stubby wings, a tiny cockpit, and no propeller, or jet engine visible. “Oh yeah, that’s the X-15,” said Martin, “it’s a rocket-powered plane. I didn’t work on it, but I thought it was interesting and got a hold of that little book that tells you all about it.”

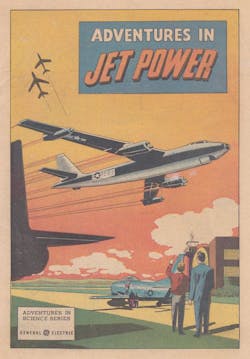

The X-15 pamphlet diverted me for several minutes as I pored over the pictures and tried to decipher the mysterious diagrams and big words that accompanied them. Rummaging a little deeper, I stumbled across what appeared to be a comic book, except that it had a picture of a pair of kids and what looked like a pilot, smiling and watching a jet taking off.

Comic Book Lesson

I struggled with the title on the cover. “Jet pro… propull…” I stumbled. “Propulsion,” said Martin softly, “that means jet engines.” We sat down and read part of the comic, a marketing item from General Electric*, probably written for kids four or five years older than I was. My uncle took time to explain how air moved through the turbine, was squeezed together, sprayed full of fuel, and burned in the far end of the engine to make the thrust needed for flight.

Beneath the papers lay a bunch of more tangible treasures, including a small set of drafting tools, a hand-carved wooden race car that was propelled by a small rear-mounted model airplane engines, several more model airplane engines, and a bunch of other model parts.

The box came home with me that night and remained one of my greatest treasures throughout my childhood. Much of what was in there was way over my head when I first got it, but I immediately understood that the yellowed photo of the Gee Bee racer, a short, stubby racing plane from the 1930s with an improbably big engine, was something special. There were other photos of famous airplanes, booklets on different technical topics, and even a set of plans for a scale model of a Pitcarin Gyroplane, waiting for someone like me to discover them.

Over the next few years, my reading improved, and the box slowly revealed its secrets to me as I regularly re-examined its contents. Terms like “airfoil,” “turbojet,” “stall speed,” and “aspect ratio” began to creep into my otherwise-normal 6th-grade vocabulary.

6th grade was also the year that I found myself at the Wellsville Municipal airport with some money I’d earned on my paper route, negotiating with the guy behind the desk for my first flight lesson. Without going into details, the instructor did his best to scare the daylights out of me on that first half-hour ride, but it didn’t matter—I was hooked. That summer, what little of my savings I didn’t spend on a couple more lessons was spent going to county fairs and riding the most violent rides I could find until I was completely acclimated to the bumps, swoops, and tumbles I’d experienced in the airplane.

Thanks to the push I got from that the box in Uncle Martin’s basement, I eventually found myself building model airplanes, and then my own ultralight aircraft (a Kolb Ullltrastar), and eventually earning a pilot’s license. Along the way, I also picked up an engineering degree that turned out to be my ticket to a job building the Mars Observer, a spacecraft that NASA sent to Mars in 1992.

One of the happiest memories of my life is standing with my Mom, my Great Aunt Esther, and of course, Great Uncle Martin (84 at the time), on the causeway at Cape Canaveral on launch day. From there, we screamed ourselves hoarse as the Titan rocket lifted off with the Mars-bound spacecraft I’d helped build.

Making My Own Box

I never forgot Martin’s box and, when I first started building spacecraft, I started assembling one of my own. Over the years when I worked in aerospace, I packed my box full of cool photos, brochures about satellites and launch vehicles, and even small bits and pieces of thermal-blanket and other spacecraft hardware I managed to cadge from the company's trash. I wasn’t sure exactly why I was packing all that stuff away in my basement, but it seemed like an important thing to do.

Eight years after I started collecting, my box saw its first service when I taught a space camp session to a bunch of local teenagers. It served as a fine supplement to the videos, field trips, scratch-built models, and other more conventional teaching aids.

A few years later, when my daughter Anwyn was born, I was eager to give her the chance to rummage through my treasures and see if they'd capture her imagination. To my disappointment, horses, and not my dusty old box, were the thing that captured her imagination and fueled her dreams.

But, while flight had been my passion, supporting hers made my world bigger and even more interesting. Some of my happiest memories are spending Saturdays at the stable watching her become quite proficient at riding, caring for, and becoming fluent in the complex, unspoken language of horses.

Since then, I've let that old box keep collecting dust in the basement, making an occasional new addition to its contents, and waiting for the right kid to come along and take it home. Although many children are out there and only one box, I felt confident that it would eventually find its way into the right hands.

A couple of decades flew by before my faith was rewarded when one of Martin and Esther's daughters contacted me to say that I have a young cousin who has a fascination with space flight. It's been a thrill to share some of what their wonderfully weird grandfather shared with me.

May the spirit of Uncle Martin's box lead her to many voyages of discovery.

*NOTE: That comic was part of a series called "Adventures in Jet Power.” You can find digitized copies of several issues here: https://digitalcomicmuseum.com/index.php?cid=62.

Did you have someone like my Uncle Martin? Would you like to share what they did to make your world bigger, more interesting, and full of wonder with me, and your fellow readers? Please comment on this story or write me at: lgoldberg(at)green-electronics.com.

This article is in the Electronic History topic within our Series Library