Methods of medical drug delivery are reaching science fiction levels. For instance, some of today’s pills can text medical professionals to tell them that their patients have taken their medicine. Also, women now can have a wireless chip implanted in them for contraception.

Take Two of These and Text Me in the Morning

According to the United States Department of Health and Human Services, five out of six Americans aged 65 and older take at least one medication daily, and almost half take three or more. With so many prescriptions to remember, these patients sometimes forget to take their medicine. Pills that use texting to notify medical personnel that they have been taken can save lives.

How is the text sent? Enter Proteus. No, not the sea god from Greek mythology or the microscopic submarine in the film Fantastic Voyage. This tiny sensor can be embedded in pills and then swallowed. Developed by Proteus Digital Health, the sensor is activated and powered by the hydrochloric acid, potassium chloride, and sodium chloride that form stomach acid (Fig. 1).

When certain dissimilar elements are immersed or embedded in an ionic solution, they create power. Proteus Digital Health has taken two fundamental and required dietary elements, copper and magnesium, and embedded them in a tiny sensor that is less than 1 mm square.

After the pill is ingested, the stomach acid acts as the ionic fluid. This creates sufficient power for the sensor to link with and communicate to an adhesive patch worn by the patient.

The patch communicates all the patient’s data to a server that then can be accessed by phone, tablet, or PC by medical professionals or designated members of the patient’s family. The data will include a description of the medicine taken, the dosage, and what batch it was issued from.

The system also can analyze what effects the medicine is having—or, in some cases, not having—whether it’s been prescribed at the right dosage, or if it simply isn’t working. This information can be crucial for people who have cardiac conditions or diabetes, significantly reducing healthcare costs and possibly saving lives.

Getting Turned On

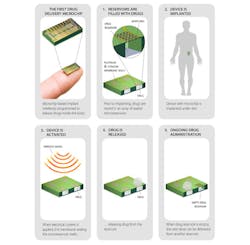

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has created a computerized contraceptive chip that can be implanted below the skin. Women can wirelessly activate it or deactivate it for up to 16 years, giving them convenient control over when they attempt to conceive.

About the size of a thumbnail, the chip releases a small dose of the hormone levonorgestrel, which is commonly used as an oral contraception. The levonorgestrel is held within the device in minute compartments and kept in place by a thin platinum and titanium seal. A small electrical charge melts the seal to release a 30-µg dose into the woman’s body automatically and daily unless the chip is deactivated (Fig. 2).

While this on-off facility is very convenient, it does raise concerns about system security, i.e., could somebody else turn the system off? Could it become a target for hacking pranksters?

Not surprisingly, the developers insist the system is secure thanks to its algorithms and data encryption. Also, communication has to occur at skin level, further preventing inadvertent or pernicious interference.

But how reliable will the device be in mechanical terms? Currently, no studies can emulate what 16 years of being housed in the human body might do to the chip. Plus, 16 years equals 5840 daily doses of levonorgestrel, and that’s a lot of operations that have to consistently and accurately maintain 30-µg doses.