Autonomous Cars Face a Slew of Sensory, AI, and Communications Challenges

Object-detection, communication, navigation, safety, and security are just a few of the challenges facing autonomous car makers. Many of these require advanced sensory and communications technologies, as well as advances in artificial intelligence (AI).

Presently, intelligence-based features on “semi-autonomous” cars include adaptive front lighting, lane departure warning, adaptive cruise control, self-parking, blind-spot detection, and emergency assist braking. But getting to the next level of truly driver-less autonomous cars requires greater use of AI, a robust global navigation satellite system (GNSS), and advanced sensing capabilities—tasks that are much more complex and challenging.

Sophisticated mapping and data analytics are needed for autonomous vehicles to be effective. The challenges will be even tougher for overseas car makers whose roadways and regulations are totally different from those in the U.S. and Canada. Car companies must also get legislative approvals to survey roadways and show studies on what affects the communities involved where such mapping occurs.

This hasn’t deterred the automotive industry, as it develops more partnerships with hardware and software companies to develop technological building blocks for what it sees as new market opportunities beyond the transportation of passengers. They see market opportunities in using data that enables the concept of smart vehicles for new business opportunities.

They recognize that consumers, particularly younger drivers, are increasingly using smartphones and other smart devices to work at home, telecommute, and ride-share—as well as locate, hail, and rent vehicles—rather than outright purchase a car. As a result, car companies are gearing up to adjust to a shifting landscape of the automotive industry.

Indeed, the two top ride-share companies, Uber and Lyft, are eagerly working on a fully autonomous car, as is Apple.

Many Sensor Types

An array of sensor types exists for autonomous cars, each of which has its pros and cons. The three most popular ones are radar, lidar, and cameras. Radar is very accurate for the determining the velocity, range, and angle of an object. It is also more costly than cameras. Lidar is the most costly and is excellent at 3D mapping of objects.

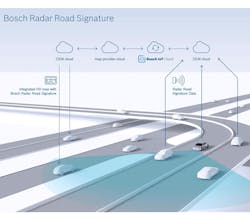

For car makers, cameras seem to be the most cost-effective approach for self-driving vehicles. But not everyone agrees. For example, Bosch is developing a Radar Road Signature technology to create high-resolution maps for autonomous cars. A “signature” refers to the individual reflection point of the radar signal. Signals are compiled to create the map that allows the car to identify its position within a driving lane (within centimeters, according to Bosch).

There is a lot of work going on in lidar to bring down costs. Silicon Valley startup Luminar Technologies is working hard to do so with a product that sends millions of laser pulses/s that gives a vehicle a 120-deg. range of view. “A lot of self-driving vehicles like delivery and warehouse robots are limited to operating at or below 25 miles/hour,” said CEO and founder Austin Russell. “With our product, we can see objects at 200 meters while driving 75 miles per hour…That means you can have about seven seconds of time for the car to react, while other lidar sensors give only one second of reaction time.”

MEMS technology is also entering the Lidar scene with low-cost solid-state units, like the S3 from Quanergy that is said to sell for $250. Placing four of them in each car corner for a 360-deg. view brings the total cost to $1,000.

And Israel-based Innoviz Technologies is working on a MEMS solid-state lidar sensor, the InnovizOne, that is expected to be available for $100 by late 2018.

Sensor Fusion and AI

Out of all of the aforementioned sensor technologies, cameras are the most appealing due to their low cost (which is getting even lower) and high resolution (which is also increasing). Though they’re passive devices and are susceptible to variations in weather and lighting conditions, this can be overcome by using multiple cameras with an AI-based GNSS—so as to make adjustments via software loaded into an IC microcontroller and achieve sensor fusion. NXP Semiconductors has identified adaptive cruise control, automatic high beam control, traffic-sign recognition, and lane keep systems as examples of advanced driver assistance systems (ADASs). However, more low-cost and sophisticated sensory advances are still needed.

TDK, which acquired InvenSense, one of the largest makers of MEMS gyroscopes for measuring motion and rotation, is eager about sensor fusion. InvenSense acquired Movea, a sensor fusion firm, back in 2014. TDK has built magnetic sensors that measure angles in train wheels and a car’s windshield wipers. These are fused with InvenSense’s gyroscopes and inertia technology.

As Tim Kelliher (formerly of InvenSense) told Electronic Design, there are uncertainty errors in each of the aforementioned sensing technologies that can be compensated for. Sensor fusion could turn smartphones into personal assistants not only from users, but also just walking outside or hearing a certain noise.

NXP Semiconductors, which was purchased by Qualcomm, favors sensor fusion over AI in its Blue Box for self-driving cars, which allow companies to better troubleshoot the driving software’s decisions. And Mobileye, which was bought by Intel, says that its latest vision chip can fuse data from up to 20 sensors.