As an individual patent holder, entrepreneur, engineering consultant, and expert witness in intellectual property (IP) lawsuits, I find that a lot of people have misconceptions about patents. Business owners, entrepreneurs, and politicians are making poor decisions based on bad information.

Many engineers feel that lawyers and judges do not understand technology and invention, leading to bad rulings and litigation. In my experience, it is correct that judges and juries often do not understand technology, but lawyers and engineering experts like me are the ones who guide them.

This file type includes high resolution graphics and schematics when applicable.

The lawyers with whom I work almost always have engineering degrees and worked for years in industry before going back to law school. The job of an expert witness is to explain complex technological issues to a nontechnical judge or jury. Does the system work perfectly? No more so, but also no less so, than any other aspect of law that, by its nature, is prone to human interpretation and misunderstanding.

What Is a Patent?

According to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), “A patent is an exclusive right granted for an invention, which is a product or a process that provides, in general, a new way of doing something, or offers a new technical solution to a problem. To get a patent, technical information about the invention must be disclosed to the public in a patent application.”1

A common misconception is that a patent is meant to give an unfair advantage to someone. In fact, the opposite is true. A patent allows inventors to share their invention with the world yet have it be protected from use by others without their approval and compensation. Even if others created the same invention independently, they must obtain a license from the patent holder.

Without patents, inventors would keep their inventions secret to prevent competition. When the inventor died, the principles behind the invention would also die. Technology would stagnate. This is at least part of the reason that the principles behind many great ancient inventions have been lost even to this day.

By granting patents, governments tell inventors that they must describe to the public exactly how their invention works so others can use it, improve it, build upon its principles, and even find ways around it, all to further improve technology and spur innovation. In return for this full disclosure, the government gives the inventor a limited amount of time to completely control the use of the invention.

Are Patent Terms Too Long?

No. Detractors argue that technology moves so quickly that a 20-year patent term is too long to be effective. They argue that patent terms should be shorter, which would somehow increase innovation by putting patented inventions into the public domain (i.e., make them available to anyone without a license from the inventor). This argument is nonsensical.

If technology advances so quickly, then a 20-year term or a 100-year term would not matter because a new technology would come along, rendering the old technology, and all related patents, worthless. The argument to shorten patent terms is simply a red herring put forth by those who actually believe that technology does not move as quickly as they claim, and they want to be able to use another’s inventions without paying licensing fees.

Are Patents Being Given to Simple, Obvious Things?

Sometimes, yes. I have read many patents over the years. Some of them are simple or obvious or systems and methods that have been well known in the field for years but no one bothered patenting them. But is this the problem that it is made out to be? No.

Clients have hired me to look over their patent portfolio, and I have identified these poor quality patents. They make nice plaques on the wall, but they are not useful to license or to litigate. I tell my clients that I cannot support the validity of these patents because the technology was well known or obvious at the time the patent was filed. They may be able to find someone with less experience in the industry who thinks the invention was novel, though. Or, they may be able to find someone who will tell the judge and jury anything they are paid to say.

But if the other party hires someone like me, someone who is halfway knowledgeable and experienced, that expert will be able to produce mounds of evidence that the patent is invalid, destroying the patent holder’s case and costing the holder a lot of money. What would be the point in doing that? Of course there are frivolous cases in every kind of litigation, including patent litigation. But they are rare because they are just too risky to bring to court. The plaintiff has too much to lose by litigating a poor quality patent.

Now before you get ready to send me an angry list of all the “stupid patents” that have been litigated recently, consider this. Can you understand an engineering paper by its title alone? Can you understand electronics by reading the title of an electronics text? In the same way, you cannot understand a patent by only reading the title. In fact, nothing in patent law requires the patent title to have anything to do with the invention. I personally have patents where the title is almost meaningless.

When I started writing the patent, I had one concept in mind. When I finished writing it up, weeks or months later, the key concept had become clearer. Then after years of battling with the patent office, I realized that the key aspects of my invention were different than I had originally envisioned. When I filed continuation patents, which identify other novel aspects of my invention, I kept the same title for convenience. So do not judge a patent by its title. You need to read the entire thing, and in particular you need to understand the patent claims, which are the essence of the invention.

Are Patent Trolls a Gigantic Threat?

No, they are not. The term “patent troll” is used generically as a pejorative label for entities that assert and litigate patents that someone does not like. Is a “patent troll” a company that sends threatening letters to small mom-and-pop stores to pay $1000 or risk a lawsuit? Is it a company that went bankrupt and is now trying to compensate its investors by licensing its patents? Is it a university performing state-of-the-art research and guarding the results of that research? Is it a large company collecting low-quality patents and using them to extract license fees from deep-pocketed corporations? Is it a corporation buying up patents from individual inventors that do not have the resources to manufacture their inventions or to license them to large companies? There is no accepted definition. This is not by accident but rather by design.

Those who attack the patent system want to lump all of these entities into a single category and label them as “patent trolls.” Most people will see at least one of these entities as a bad actor, leading them to condemn all of them. Interestingly, groups that oppose all IP rights and believe that “information should be free” have teamed up with huge corporations on this issue. But these ideologically opposed groups are united on this issue for very different reasons.

The groups that oppose IP rights and do not believe in free market capitalism are doing it because they believe that there is no such thing as IP and have found the “patent trolls” argument to be a convenient way to chip away at IP rights. The large, established corporations want to hold onto their markets and do not like the small inventor or startup entrepreneur who can take it away from them using patents for novel inventions. Many large corporations have begun banding together to fight so-called “patent trolls” by pooling their resources and licensing their patents among themselves.

One previous similar group that was formed to fight “patent abuses” was the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers (ALAM) in 1903, which proudly claimed, “It will not try to shut out reputable and established manufacturers who build a reliable vehicle; it will license all such, but it will license no unreliable upstarts. In this way the association will protect the public and be a boon to all purchasers of gasoline automobiles.” One such unreliable upstart that it was referring to was Henry Ford.2

Are Patents Destroying Innovation?

No. This is a ridiculous assertion, but I hear it often. Many critics of the patent system will tell you that the system used to work when developments were slow and before modern technology existed. But an examination of history will tell you that these arguments have been around for a long time.

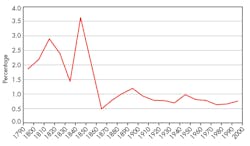

Litigation rates for patents relative to the number of patents issued were much higher in the era before the Civil War and during the subsequent market expansion that started in the 1870s than they are today (Fig. 1).3 This was the time of the railroads and the industrialization of America, which could hardly be considered unproductive and not innovative.

To put litigation further into perspective, the estimated 100 patent suits that were filed in the smartphone industry as of 2012 was a much smaller number than the 587 lawsuits litigated just by American Bell Telephone Company and its successor during the first “Telephone Wars” of Alexander Graham Bell’s time.4

Measuring the effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) of patents by the amount of litigation without looking at other factors is no more correct than measuring the effectiveness of medicine based solely on the number of malpractice suits or the number of malpractice suit awards. In fact, in industries where patenting is highest, the prices of products decline the fastest.5

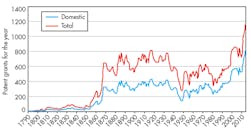

The rise in patent litigation is due to the gigantic rise in patent applications (Fig. 2). This is a good thing. Like all other areas of human endeavor, technology has made invention possible by anyone anywhere. Personal computers and smartphones have brought previously unheard-of power to the desktop and to the pocket, while the Internet has enhanced communication and allowed research that previously took weeks of library time to be done in an instant.

These technologies have also created new platforms for innovation while the software required to control these technologies, and the development tools needed to create that software, is so cheap that high school students can create groundbreaking inventions subsidized only by their weekly allowances. Invention is no longer limited to the wealthy, but to everyone, and we should recognize and celebrate this achievement as a great step forward in human history.

So, What’s Wrong with the System?

The patent system is inefficient because of the huge number of patents being filed. The solution is not to change patent laws or to restrict patents. Certainly, the solution isn’t to restrict which people or entities can own, sell, trade, license, or litigate patents. Such a solution is simply un-American, violating the principles upon which our country was founded. This would be akin to restricting real estate purchases and sales to those who live on the land.

The solution is to use technology to solve the problems that technology is creating. The patent office needs to implement much better tools for helping patent examiners understand and analyze patents, as well as to intelligently search for prior art not just among patents but among all published documents. This would enable the quick elimination of patent applications of poor quality and the quick processing of good patent applications.

Such technology has been around for years, incorporated in search engines and document analysis software, but the patent office is not using it. And it is not a question of money. Any major search engine can be used for free. Simply searching for patents on “latent semantic indexing,” one method of analyzing text documents like patents, produces 572 patents.6 Technologists should be implementing these technologies for the patent office, and legislators should be pressing for their adoption rather than overhauling patent laws.

Conclusion

Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” Historical documents suggest that James Madison wrote this clause while Thomas Jefferson and Charles Pinckney in particular lobbied for its adoption. In England at the time, only the wealthy and powerful could obtain patents.

The Founding Fathers believed so greatly in the protection of the individual from the overwhelming power of large entities that they made this a centerpiece of the U.S. Constitution. The Patent Act of 1790 was passed even before the Bill of Rights was adopted in 1791. The patent laws embody the very principles of American society for which we fought the Revolutionary War. Since then, the U.S. patent system has contributed to America becoming the most innovative society in the history of the world.

References

1. “Intellectual Property - What is a patent?” World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), www.wipo.int/patents/en/

2. M. Barger, “How Henry Ford Zapped a Licensing Monopoly,” www.fee.org/the_freeman/detail/how-henry-ford-zapped-a-licensing-monopoly

3. B.Z. Khan, “Trolls and Other Patent Inventions: Economic History and the Patent Controversy in the Twenty-First Century,” http://cpip.gmu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Khan-Zorina-Patent-Controversy-in-the-21st-Century.pdf

4. K. Lustig, “No, the Patent System Is Not Broken,” www.forbes.com/sites/forbesleadershipforum/2012/02/09/no-the-patent-system-is-not-broken/

5. S. Haber and R. Levine, “The Myth Of the Wicked Patent Troll,” http://online.wsj.com/articles/stephen-haber-and-ross-levine-the-myth-of-the-wicked-patent-troll-1404085391

6. United States Patent Office, “Results of Search in AppFT Database for: ‘latent semantic indexing,’” http://appft.uspto.gov/netacgi/nph-Parser?Sect1=PTO2&Sect2=HITOFF&p=1&u=%2Fnetahtml%2FPTO%2Fsearch-bool.html&r=0&f=S&l=50&TERM1=latent+semantic+indexing&FIELD1=&co1=AND&TERM2=&FIELD2=&d=PG01

Bob Zeidman is the president and founder of Software Analysis and Forensic Engineering Corporation, the leading provider of software intellectual property analysis tools, having pioneered the field. He is also the president and founder of Zeidman Consulting, a premier contract research and development firm in Silicon Valley that provides engineering consulting to law firms regarding intellectual property disputes. He is the recipient of the 2010 Outstanding Engineer in a Specialized Field for Innovative Contributions in the Area of Forensic Software Analysis from the IEEE Santa Clara Valley Section. He also is the author of the book The Software IP Detective’s Handbook: Measurement, Comparison, and Infringement Detection. He holds numerous patents and two bachelor’s degrees, in physics and electrical engineering, from Cornell University and a master’s degree in electrical engineering from Stanford University. He can be reached at [email protected]

About the Author

Bob Zeidman

President and Founder

Bob Zeidman is the president and founder of Software Analysis and Forensic Engineering Corporation, the leading provider of software intellectual property analysis tools, having pioneered the field. He is also the president and founder of Zeidman Consulting, a premier contract research and development firm in Silicon Valley that provides engineering consulting to law firms regarding intellectual property disputes. He is the recipient of the 2010 Outstanding Engineer in a Specialized Field for Innovative Contributions in the Area of Forensic Software Analysis from the IEEE Santa Clara Valley Section. He also is the author of the book The Software IP Detective’s Handbook: Measurement, Comparison, and Infringement Detection. He holds numerous patents and two bachelor’s degrees, in physics and electrical engineering, from Cornell University and a master’s degree in electrical engineering from Stanford University. He can be reached at [email protected].