Stop the Copycats: Reasons for Choosing Design-Patent Protection

This file type includes high-resolution graphics and schematics when applicable.

In this term, in the U.S. Supreme Court, Apple and Samsung argued a case that brings to the forefront a lesser-known type of intellectual-property (IP) protection: design patents. While most companies are well-versed in the value of utility patents, many have yet to discover that design patents can be an equally important component of their IP portfolio. Design patents can help prevent knockoffs, obtain faster patent protection, save money, and more.

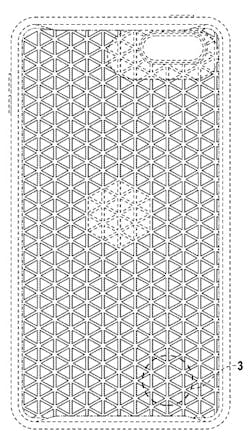

The most popular type of patent, a utility patent, protects the structural and functional aspects of a new or improved product or system. A design patent, on the other hand, covers the unique appearance of an item. A design patent includes elements such as a specific product shape, color arrangement, or surface ornamentation. For example, the shape of a sports car or a surgical instrument may be protected with a design patent, and likewise a smartphone case with a new surface pattern (see figure).

Other important differences exist between design and utility patents. A design patent itself consists primarily of drawings with little text other than brief descriptions of each drawing orientation and explanations of the drawing conventions used. A utility patent, on the other hand, routinely includes many columns of text that describe the various embodiments of an invention, and ends with one or more claims that define the scope of the invention. A design patent has only one claim—a short characterization of the illustrated device, such as “the ornamental design for a medical device as shown and described”—and like a utility patent, may be directed at only a part or subassembly, rather than the device as a whole.

A design patent is in force for 15 years from the date it issues as a patent, whereas a utility patent has a term of 20 years (with some exceptions) as measured from the filing date. Once a design patent is issued, no further action is required to keep it in force. In contrast, to keep a utility patent in force, maintenance fees must be paid on three separate occasions to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). These fees are due four years, eight years, and 12 years after the issue date. Failure to pay any of the maintenance fees will cause the utility patent to lapse.

Utility and design patents can play an enormous role in your company’s success, so it might be worthwhile from a strategic standpoint to diversify your IP investment with design protection. Consider the following reasons to pursue design patents.

Protecting Your Investment

A product’s design can critically impact market acceptance and success. For example, Apple has argued in court that the iPhone’s success is due not only to its technical features, but—at least in part—to its appearance. And in the Apple v. Samsung case, the damages awarded for design-patent infringement were hundreds of millions of dollars more than awarded for utility-patent infringement.

When it comes to patents, a product may include innovative technical features that are covered by a utility patent, but the look and feel of the product may warrant design-patent protection. In some cases, such as when the technical features are outdated, utility protection may not be available. However, if you recast an old product in a new design, it may be possible to protect the new design with a design patent. For example, headphones have been around for years, but if even just a portion of the headphones is redesigned, it may be possible to protect them with a design patent.

Preventing Knockoffs

A competitor or knockoff artist may want to sell an item that looks just like your company’s product, taking advantage of the technology, customer service, or branding that distinguishes your product in the marketplace. Particularly for over-the-counter consumable products, a customer may not take the time to discern the genuine product from an imitator’s product. If the similar product doesn’t incorporate a technical innovation covered by one of your company’s utility patents, then there may be no utility-patent infringement. However, there may be design-patent infringement.

Getting Protected Faster

Design patents tend to be issued more quickly than utility patents. While it’s common to wait two years or more before the USPTO reviews your utility application, design-patent application examination timelines are typically shorter, with design patents generally receiving a first review within just over a year. In fact, some patents are even issued within a year. As such, filing a design patent may be beneficial if you have a product quickly entering the marketplace.

Cost Savings

A design-patent application typically costs much less to prepare and prosecute at the USPTO than a utility application. For a design application, an attorney decides what figures to prepare, and an illustrator, known as a patent draftsperson, prepares the figures. Minimal time is required from the attorney to prepare the text of the design application. In contrast, a utility application generally requires substantial amounts of text and claims drafting, and therefore requires more time and expense to prepare.

Once design and utility applications are filed at the USPTO, examiners will review the applications. Frequently, an examiner grants the design patent after the first review of the application, whereas utility applications are typically reviewed by the examiner several times before reaching a favorable outcome.

Quicker Settlements

Remedies for design-patent infringement are stronger than those offered for utility-patent infringement. For example, a prevailing design-patent plaintiff can recover all of an infringer’s profits for selling the offending design. A utility-patent owner, in contrast, typically recovers only a reasonable royalty for infringement or, in certain circumstances, its own lost profits. A utility-patent owner isn’t permitted to recover the profits of the infringer. As a result, in instances of an alleged design-patent infringement, the threat of losing all profits may motivate the infringer to seek a quick settlement.

Advantages Over Trade Dress

Some may wonder whether design-patent protection is overkill if a company intends to rely on trade-dress rights, a form of IP similar to trademarks that also protects the look and feel of a product or its packaging. To recover for trade-dress infringement of a product’s design, however, one must first establish that the trade dress has obtained “secondary meaning” or “acquired distinctiveness” in the marketplace. In other words, one must show that the public has come to associate the product design’s trade dress with a particular producer of the goods.

Although trade-dress protection is valuable, it typically takes at least several years and considerable advertising and marketing expenditures before the requisite secondary meaning or acquired distinctiveness can be established. Consequently, during at least the first few years after a product launch, if not longer, no trade-dress rights are available to stop copycat products. On the other hand, a design patent is typically granted long before this evidentiary hurdle can be met, enabling the design-patent owner to deal immediately with infringers.

Utility patents will always be a valuable component of a company’s intellectual-property strategy. However, for reasons detailed in this article, it’s essential that companies also consider design patents to protect the unique design elements that distinguish their product from their competitors’ products. A combined strategy of filing for both utility and design patents will protect not only the functional aspects of a product, but its unique appearance as well.

Eric Amundsen and Jason Honeyman are shareholders and Andrea Merin is an associate in the Mechanical Technologies Practice at Wolf Greenfield, an intellectual property law firm in Boston. They can be reached at [email protected], [email protected], and [email protected], respectively.