Qualcomm Buys NXP for $47 Billion, Turning Eyes to Internet of Things

After years of twisting and turning its mobile chips to fit inside new devices, Qualcomm has made the clearest statement yet that its future lies beyond smartphones.

The chipmaker said Thursday morning that it had agreed to buy NXP Semiconductors for $47 billion, betting the company's future on chips that connect and computerize everyday products like cars and thermostats. It is the largest deal in the history of the chip industry, outpacing the other astronomical deals that have been announced in recent years.

The acquisition will give Qualcomm instant access to a wide array of technologies outside its normal field of expertise. NXP, which is headquartered in the Netherlands, makes billions of dollars selling chips to car manufacturers and makers of industrial equipment for factory floors. For years, Qualcomm has focused on making the intestines of smartphones.

The deal also underlines the vision of Steve Mollenkopf, Qualcomm's chief executive, who views the circuitry inside smartphones as increasingly vital to other industries. The San Diego-based chipmaker has already dipped its toes into robotics and automobiles by tweaking the design of its popular Snapdragon processors.

“The NXP acquisition accelerates our strategy to extend our leading mobile technology into robust new opportunities, where we will be well-positioned to lead by delivering integrated semiconductor solutions at scale,” Mollenkopf said in a statement.

In a conference call with analysts on Thursday, he said that the deal gives Qualcomm all the vital organs required for the Internet of Things, or connecting tiny computers inside everyday products to the internet. He added that the company already had experience in selling processors and wireless chips for phones.

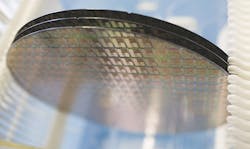

NXP is one of the biggest suppliers of microcontrollers – miniscule squares of silicon used in everything from windshield wipers to printers – and near-field communication chips, which enable mobile phones and wrist bands to wirelessly interact with credit card terminals. It also sells the secure chips used inside credit cards.

“The world’s information is in the hands of billions of people because we have computers in our pockets,” Mollenkopf said. Within the next decade, he said, Qualcomm would be “interconnecting their worlds and everything around them.”

One of Qualcomm’s biggest bets is that automobiles will become more and more like smartphones. The company is not a complete stranger to that market, having released chips that provide computer vision, digitize dashboard gauges, and connect to cellular networks and other cars. But it has seemed like an afterthought in recent years, overshadowed by Qualcomm’s lucrative business of making smartphone parts.

NXP's focus is vastly different. It is the largest maker of automotive chips, making technology for connecting cars to traffic lights, fusing information from cameras, powering touch screens, and enabling cars to automatically avoid collisions. On Thursday, NXP reported that it had earned $853 million from its automotive business in the third quarter of this year, accounting for around 40% of its entire revenue.

Other companies are buying into the automotive business. In July, Analog Devices spent $14.8 billion to acquire Linear Technology and its wide range of circuitry for electric vehicles and factory equipment. Last month, the Japanese microcontroller giant Renesas paid $3.2 billion for Intersil, which makes power management chips, in an attempt to get back on top of the automotive market.

Richard Clemmer, NXP's chief executive, was involved in a similar deal. Last year, the Dutch chipmaker bought Freescale for $11.8 billion, expanding into microcontrollers, networking chips, and automotive safety systems. But the deal fell short of supplying the advanced processors and machine learning critical to autonomous cars.

That was one of the reasons that NXP agreed to the deal with Qualcomm, Clemmer said. "We needed increased computing horsepower," he said, adding that the company had not started working on machine learning, like Qualcomm's Zeroth system. Working together could boost NXP's chances of competing with Nvidia and Mobileye, which have a head start in autonomous driving technology, and newcomers like Intel.

Mollenkopf, who joined Qualcomm as a chip engineer over 20 years ago, compared the deal to Qualcomm's strategy in the early days of the smartphone. Under Paul Jacobs, Qualcomm's former chief executive and the son of the company's founder, the chipmaker developed the wireless chips that tapped into cellular networks and the low-power processors that would make sense of all the data straining through the device.

Selling chips for smartphones reaped Qualcomm billions in profits, but margins have recently started slipping. The higher cost of making chips has eroded profits as the markets for personal computers and smartphones have ground to a halt. In 2015, the company started a restructuring in an attempt to significantly cut operating costs.

But for years, Qualcomm has recoiled from using its stockpiled cash for large acquisitions, instead nibbling on smaller peers in the wireless industry. In 2011, it paid $3.1 billion to acquire the Wi-Fi chipmaker Atheros Communications, and spent $2.5 billion last year on Cambridge Silicon Radio, a maker of wireless chips for cars and household devices.

Mollenkopf, who took over as chief executive in 2014, was behind both those deals. And with more than $30 billion in cash at its disposal, he had plenty of ammunition for ambitious moves.

But the latest deal raises an array of complications, including how to combine two massive work forces. Qualcomm employs around 33,000 people, according to its latest annual report, while NXP keeps around 45,000 employees on payroll to make and sell tens of thousands of products.

The deal also has the potential to fundamentally upend Qualcomm’s identity. The company will be forced to grapple with its fabless model, in which it pays manufacturers to make its mobile processors and licenses patents for its wireless chips. On the other hand, NXP runs 14 chip factories in the United States, Asia, and Europe. It is not clear how Qualcomm will rectify those different business models.

Mollenkopf said that NXP executives would remain in charge of the factories, mitigating any awkwardness. He also suggested that Qualcomm was not completely new to manufacturing. It has gained some know-how through a new company it formed with Japan's TDK, which is creating new types of wireless filters.

Qualcomm will also become something of a nesting doll for other complicated corporate deals. NXP is still digesting its acquisition of Freescale and transferring its standard products business, which made discrete semiconductors and power transistors, to Chinese investors. Qualcomm has been restructuring since 2015.

Qualcomm’s courtship was first revealed almost a month ago, when the Wall Street Journal reported that the companies were in talks. The deal is expected to close by the end of 2017.

About the Author

James Morra

Senior Editor

James Morra is the senior editor for Electronic Design, covering the semiconductor industry and new technology trends, with a focus on power electronics and power management. He also reports on the business behind electrical engineering, including the electronics supply chain. He joined Electronic Design in 2015 and is based in Chicago, Illinois.