Sustainability: A Movement Unto Me

What you’ll learn:

- Real-world sustainability problems can be identified for engineers to solve by being aware of the human condition and improving it.

- One engineer’s sustainable solution can reduce energy use worldwide and improve quality of life.

- Life is not immortal: The life event that creates this epiphany may not provide enough time to leave a social and environmental legacy as rationale for, and evidence of, your existence.

Poor Thais in the dark,

Light bulb turns on in my head...

Flat LED lamp is born

February is sustainability month at Electronic Design, with one of my esteemed colleagues, James Morra, spearheading the effort to deliver quality material on sustainability to our readers. In the spirit of this theme, let's kick off the month by sharing what I've done in my career with attempts at sustainability, so far.

As a practicing electrical engineer, the main focus early in my career was to produce, design, and define high-quality, successful products that fit customer need—and desire. Eventually my responsibilities would cross me over to the Dark Side of doing, yes, product marketing, along with applications engineering, strategic planning and product architecture. With those, though, I never let go of my passion for the actual design side and doing engineering itself, so I kept one toe on each side of that line in the sand, which any engineer with self-respect would draw.

In taking on my mostly-analog editor role here at Electronic Design, we reached an agreement during my hiring that I could continue my design activities and patent filings. I wasn’t willing to push words around in trade for abandoning my passion for engineering design. Besides, what good would I be to our readers if I wasn’t a current and practicing engineer?

Armani in Sandals with a Slide Rule in the Pocket

One of the biggest compliments I received in my career was our Area Sales Director taking me aside after a first meeting with a major account customer, telling me the lead engineer had whispered to him, "Before this meeting, based on his title [Director of Strategic Marketing] on the agenda, I thought Andy was a suit.” Yes, I had a habit of frying customers' engineers' brains **as an engineer** during problem-solving and product definition meetings. I was almost always sought out first by them because we always came out as partners in success vs. being mere supplier/customer.

It was in the mid-1990s that this Director of Strategic Marketing met the affable, bigger-than-life, Lee Goldberg, contributing editor for Electronic Design, who is a tree-hugging hippie at heart and is the author of one of the first books on sustainability in the electronics industry.

His sandal-footed values have rubbed off on me over the years, and birth of my quadruplets in the same timeframe of our first meeting gave me a new perspective on leaving the world better than I found it....for my kids, and, subsequently, for my granddaughter Minion and her two younger brothers.

A RIF that Made the World a Better Place

I switched jobs a few times afterwards, finding myself at Altera in Silicon Valley, and then as a marketing manager in the low-speed amplifier group at National Semiconductor. I got swept up in the 2009 economic downturn and in National's restructuring in anticipation of its acquisition by Texas Instruments, which also had an amplifier group, which led to my group getting laid off. During those days, even my colleague, Bob Pease, got RIF'd, causing an uproar among the analog community.

I took a trip to Thailand during my “employment lull,” after reading a column about being “funemployed” and having had a brush with death, health-wise, after remembering a weekend transition there on my trip to India back in my Altera days. At one of the White House press dinners a few years later, Obama quipped something like: "The other night, Michelle and I went out for some Thai food—in Thailand" (Fig. 1) after a previous attempt by the press to create scandal for their use of AF1 for personal travel.

All joking aside, my immortality got quashed, creating a greater sense of urgency for that “leaving the world better than I found it” legacy stuff.

I'm an unconventional tourist and enjoy total immersion in local cultures when I travel, usually including a weekend in my extensive business travels, which often resulted in cheaper airfares. In this instance, I found myself in a village in one of the most impoverished areas in the Northeast, commonly known as Isaan. Here, I spent several days living with the family of a friend of mine. I saw their neighbors trying to eke out an existence on $10/day with a TV and a single light bulb in the kitchen area for cooking in the evening and for the kids to be able to do school homework.

The Light Bulb Moment

At that time, the West was moving to LED bulbs, which were priced in the $45-$50 range, and DoE was banning incandescents. The electricity savings were very real with power dissipation being reduced by about 90% over that of a fellow ethnic-Croatian’s—Franjo Hanaman—tungsten-based incandescent bulb ("Edison's" carbon filament bulb was a joke and even he, who played popular media like a fiddle, quietly moved to the tungsten filament after a few years of miserable carbon-filament bulb lifetimes and light output). Hanaman’s tungsten filament would also be used to improve early vacuum-tube diodes and triodes. Tako je.

>>Check out this TechXchange for similar articles and videos

How can a family put food on the table and replace a burned-out bulb at $50—probably a month's savings of "disposable" income? It was this revelation that emboldened me to muster my multidisciplinary engineering skills, and value-engineering experience, to subsequently develop a $10 (one day's pay) light bulb. The bulb could easily be machine-manufactured locally to reduce transportation costs and emissions, as well as displace billions of power-wasting bulbs in coal-burning Asia alone.

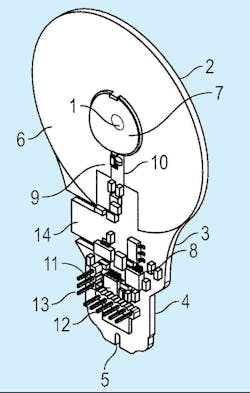

I came up with a novel, flat design (Fig. 2) based on a circuit board that minimized components to the point where it did not have a separate, expensive heatsink casting. I even included castellations in the board so that the board itself could screw directly into an Edison-bulb socket. I filed a provisional patent, entered my design into a Philips design contest (being funemployed, I could use the prize money, $60k if I remember correctly) and didn't win the contest. A plastic bag for blood won first prize.

Not so Jolly, Roger

Four months later, Philips announced its "SlimStyle" bulb (Fig. 3) as being available at Home Depot, and produced it for about three years, likely making an estimated $100M in profitable revenue. Their bulb, in the interest of time-to-market, hacked off the base containing the power supply of an existing UL-approved LED bulb. It added a circuit board with a plurality of LEDs forming a centroidal light source whose heat dissipation was by means of a flood of copper on the circuit board (how’s that for patentspeak?), and had a translucent plastic cover for shock protection and light diffusion.

A bit more than a month after the initial Philips flat bulb availability at Home Depot, I attended the annual Analog Aficionados party. The flat LED bulb prototype I brought with me was a huge hit among that august crowd, usually comprised of the who's who of analog design, including the late Bob Pease, Paul Rako, Don Tuite, and many others.

The low cost of this flat design forced everyone down from $50 to below $10 a LED bulb as a loss. Several completely exited the market, but with Philips Lighting going IPO with a profitable lighting business, then hard-stopping its manufacture one month before this also ethnic-Croatian inventor’s patent issued.

Cree Lighting also seems to have run with my flat bulb IP. However, the company used two circuit boards to increase area for heat dissipation and further improved the light pattern and its aesthetic with a vented, translucent, plastic shell in its “4Flow” and “Connected” (Fig. 4) LED bulb product lines.

With our little circuit-board invention that made LED bulbs affordable at less than $10, versus the outrageous cost-based pricing of ~$50 at the time, we started a sustainability movement. It impacted a product, industry, and power consumption, worldwide, with an affordable LED lighting solution. Even though household lightbulbs have moved on to LED "filament" lamps, a market still exists for a low-cost, integrated, machine-assembled, PCB-heatsinked, LED light source in rugged applications that include automotive lamps and headlights.

The flat bulb project cost me, my friends (including Lee), and my family over a million bucks in R&D (counting my time and patents costs), and we got nothing back so far for that $1.3M other than a set of issued patents and the satisfaction that we disrupted an industry worldwide. I, personally, got hit with a whopping dose of pride with the feedback I received from my analog design peers and from analog industry lumenaries[sic] such as the lineage of two of the personas of my, now, analog editor predecessors at Electronic Design.

My dues for existence on the planet were, finally, paid in full, and then some, after that health issue, and its continued decline for well over a decade, which made me urgently aware of my own accelerated mortality. It was, indeed, (near-starvation-based) funemployment.

Sustainability 101 for Vulcans

So, give something back, something of benefit to society and the planet, while your brain is functional and your heart still beats. Don’t suck it dry because of some heartless, hoarding, sickness for piles of cash, or because of a clinical lack of social awareness and empathy.

You can still do it because it is the LOGICAL thing to do. You can still do sustainable design, and you can voice your opinion in meetings to those in the minority who only know exploitation because you know they can’t get rid of you without major pain (Fig. 5). Boldly go where no-one has gone before...

That said, there's another decade of my development of industry-disruptive designs and patent filings for sustainability to take us to the present (yes, I still do funemployed engineering design, as well as spend my spare hours taking a whack at anti-sustainability wonks on my personal account on LinkedIn and advise others in the EV conversion community about best practices and solve some of their problems pro bono—that is, when I can find the time away from this insatiable mistress called Electronic Design).

We'll get into my more recent engineering design stuff in Part 2 of this sustainability series in a couple of weeks. Yes James, two parts—you owe me, buddy, lol.

Got a ~1,200-word, technology-deep, sustainability article you'd like to write for primarily EE readers, worldwide, to read? Hit me, or James, up (quickly) with a paragraph-length abstract with your proposal. Anytime is fine, but publishing it this month would fall into the sustainability theme and would win the race against the boney dude with the scythe.

All for now,

andy

Postscripts:

- If you didn't spot them after reading this, there are at least three entendres in the piece's title. I think I do have photos of the actual flat bulb prototype on another drive somewhere, but it’s not accessible to me as I write this.

- Not to worry, I plan to return to some hardcore chip design stuff after Part 2 is in the bag, and I will be editing some spiffy contributed articles that I invited in that area in the coming weeks. I just needed to instill enough guilt in James to have him try to write a very challenging article for the Automotive Electrification week I’m managing here for all of you in early March. It's a long shot, but if anybody can pull it off, he can. We do have a SPICE article that will be published after we finish its edits, in the meantime.

- The contributed articles for Electrification week also are starting to roll in for me to edit—a wide variety of takes on an important electric-vehicle component (sorry, no spoilers).

- If you're not already a subscriber, please sign up for my twice a week, emailed, "Automotive Electronics" newsletter (click here to subscribe), in which I try to have some interesting rabbit holes for you to go down. There's available advertiser space for it, and for the Automotive Electrification week output. Sorry for the brief wearing of my ex-marketer's hat. I find myself inadvertently having it on, unexpectedly.

- And, lastly, just a reminder to the invitees out there...this year's Analog Aficionados get-together is Feb. 15th, so don't forget to RSVP to the invitation email. I can't, unfortunately, attend this year for personal reasons but hope to be there to meet with all of you next year.

AndyT's Nonlinearities blog arrives the first and third Monday of every month. To make sure you don't miss the latest edition, new articles, or breaking news coverage, please subscribe to our Electronic Design Today newsletter.

>>Check out this TechXchange for similar articles and videos

About the Author

Andy Turudic

Technology Editor, Electronic Design

Andy Turudic is a Technology Editor for Electronic Design Magazine, primarily covering Analog and Mixed-Signal circuits and devices and also is Editor of ED's bi-weekly Automotive Electronics newsletter.

He holds a Bachelor's in EE from the University of Windsor (Ontario Canada) and has been involved in electronics, semiconductors, and gearhead stuff, for a bit over a half century. Andy also enjoys teaching his engineerlings at Portland Community College as a part-time professor in their EET program.

"AndyT" brings his multidisciplinary engineering experience from companies that include National Semiconductor (now Texas Instruments), Altera (Intel), Agere, Zarlink, TriQuint,(now Qorvo), SW Bell (managing a research team at Bellcore, Bell Labs and Rockwell Science Center), Bell-Northern Research, and Northern Telecom.

After hours, when he's not working on the latest invention to add to his portfolio of 16 issued US patents, or on his DARPA Challenge drone entry, he's lending advice and experience to the electric vehicle conversion community from his mountain lair in the Pacific Northwet[sic].

AndyT's engineering blog, "Nonlinearities," publishes the 1st and 3rd Tuesday of each month. Andy's OpEd may appear at other times, with fair warning given by the Vu meter pic.