This article is part of Ada and SPARK series in the Embedded Software section of our Series Library as well as the TechXchange on Rusty Programming.

Download this article in PDF format.

Looking at programming languages, it seems that for a long time, safety or reliability was considered an afterthought, usually covered later in tools such as testing and static analysis, rather than in the language itself. However, over the past few years, it seems there’s been a growing realization that much higher levels of reliability could be achieved for a fraction of the cost if the programming language were designed with reliability in mind. Two names come to mind here: Rust and SPARK.

Rust is probably the most notable indication of the growing need for languages with safety in mind. Sponsored by Mozilla and used in the experimental Servo browser, the language was developed as a response to the inability to identify a suitable language for safe software development. Since then, several other projects have adopted this language, mostly in the IT domain.

Coming from an A&D perspective, it is intriguing to see that the Ada language wasn’t considered as a suitable starting point. In particular, looking at the Rust mission statement as expressed today in its documentation:

“Rust is a systems programming language focused on three goals: safety, speed, and concurrency. [...], making it a useful language for a number of use cases other languages aren’t good at: embedding in other languages, programs with specific space and time requirements, and writing low-level code, like device drivers and operating systems. It improves on current languages targeting this space by having a number of compile-time safety checks that produce no runtime overhead, while eliminating all data races. [...]”

One can find some troubling similarities with the Ironman requirements from the DoD that led to Ada:

“The language shall provide generality only to the extent necessary to satisfy the needs of embedded computer applications. Such applications require real time control, self-diagnostics, input-output to nonstandard peripheral devices, parallel processing, numeric computation, and file processing. [...] The language should aid the design and development of reliable programs. The language shall be designed to avoid error prone features and to maximize automatic detection of programming errors. [...] The language design should aid the production of efficient object programs. [...]”

These two extracts, separated by more than 30 years, seem to be targeting the same set of needs. Emphasis is on safety and targeting embedded environments, with efficiency and real-time responsiveness in mind. It’s not as if these are core criteria of all languages. Other languages may put the emphasis on developer productivity, integration with scientific computations, or dynamic capabilities.

And as it turns out, while Rust was being developed, another effort was undertaken by a different community, also trying to raise the bar in terms of safety. The SPARK language is an evolution of the Ada language that aims at providing a technology suitable for automatic analysis and verification.

It’s extremely interesting to see that different communities recognized the need to improve the state-of-the-art technology related to software reliability. Rust and SPARK are definitely two initiatives in the forefront of this trend. Let’s look at what each has to say.

As a disclaimer, this article is written with an Ada/C++/C#/Java background, and probably more familiarity with SPARK patterns than with Rust’s—though fascinated with what Rust brings to the table.

What Brings Them Together

To simplify the comparison, we’re going to disregard syntactic differences. SPARK is based on Ada, inspired by Pascal, while Rust is loosely closer to C. That’s that. They’re both imperative languages, compiled directly into object code, and both manage memory directly (i.e., no garbage collection). Each provides abstractions for the usual programming paradigms (procedural and object-oriented). In addition, they both offer advanced concurrency models, providing assurance of properties such as absence of race conditions.

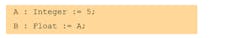

Both languages implement a number of static and dynamic checks directly in the language definition. For example, they implement strict-type safety; that is, objects can’t be implicitly converted from one type to the next. The following doesn’t compile in SPARK:

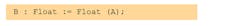

But will with a conversion:

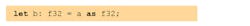

Similarly, in Rust:

will not work, but can be fixed with a conversion:

Arrays are treated as first-class citizens in both languages. In particular, equality between arrays is an equality between values, and arrays are provided with high-level initialization (aggregates) and syntax to refer to subsets of their elements (slices).

Each language enforces strict safety-related rules, but allows the developer to relax them by using explicit “unsafe” operations. In both cases, this helps to make these operations visible (and thus prime suspects in case of problems) while still allowing the right level of flexibility.

Rust and SPARK Memory Models

SPARK and Rust treat dynamic memory in two ways: the “safe” way and the “unsafe” way. The objectives of both memory models, however, are different. While both consider safety, Rust focuses on memory integrity, providing a model that allows the use of dynamic memory without risk of memory corruption. SPARK focuses on analyzability and provability of program properties and doesn’t permit direct use of dynamic memory or even pointers. Instead, it provides support for the most common cases where pointers are usually needed, specifically for containers and objects of dynamic size, and leaves other uses to the unsafe portions of the code. Both languages forbid memory aliasing in their safe subsets, and neither provides garbage-collection capability.

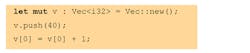

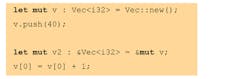

These models are unusual enough to deserve a couple of examples to illustrate them. Let’s start with Rust. To clarify up front the issue of containers (we’ll discuss them more for SPARK), Rust provides a native extensible vector type with checks:

The above will lead to the value 41 in v[0]. Access to an element that’s not available (for example, v[1]), will lead to a clear error, a panic. There’s no risk of accessing an unallocated piece of memory. Note that the vector doesn’t need to be manually deallocated. Regardless of the underlying implementation (most probably will have some dynamic memory and pointers lying around), it will be freed when reaching the end of its scope.

The Rust memory model shines when looking at how it handles arbitrary references and dynamic memory. The core idea is that a piece of data is always owned by a variable (a binding, in Rust lingo) and only one. This protects against two problems, the first of which is aliasing. A common problem arises when manipulation of a variable modifies another variable at the same time because they point to the same piece of data. A typical example of this kind of problem is double deallocation, although aliasing can also cause other subtle bugs. This situation can’t arise in Rust.

The other common problem relates to memory leaks or, more generally, the overall deallocation policy. Because a piece of data is always owned by a binding, when that binding goes out of scope, we know it’ll never be accessed by anything else (there are no other references or aliases). It can thus be safely freed.

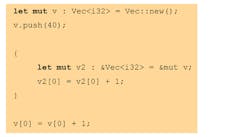

To fully appreciate the consequences of this, let’s look at a short example:

v2 is a reference (or pointer) to v. Because of the assignment, v2 borrows the value of v and owns it for the rest of the scope. As a result, it’s no longer possible to directly modify v. This is checked statically, and the compiler will refuse to compile the above code. Borrowing can be done on a smaller scope as well. For example:

When the above code works correctly, v2 releases the ownership of v at the end of the scope. This is particularly useful in parameter passing.

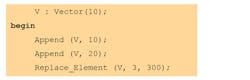

With SPARK, large chunks of memory have to be managed through dedicated containers. You can use either real-time embedded containers—typically of fixed capacity—or unbounded containers. The key idea is that containers not only provide safe access to a pool of objects from a memory perspective, but they allow ways to reason about them and statically verify certain run-time properties. Let’s take one example, one with a fixed capacity container:

The example creates a vector with a maximum capacity of 10 elements; then adds two elements to it (10 and 20). Subsequently, we attempt to replace the element at index 3. By default, vectors are indexed starting at 1 in SPARK (although other indexing is possible). Therefore, after adding two elements, only items 1 and 2 are present. The normal behavior of this code would be to raise an exception at run-time, which it will.

However, the SPARK formal prover is able to verify that the condition “the index of the element must exist before a replacement” cannot be verified, and will actually issue an error statically. In this example, the mistake is quite obvious to the careful reader.

SPARK unleashes its full power when working on larger pieces of code, making sure that certain categories of errors don’t happen, such as buffer overflow or division by zero. In other words, as soon as there’s a possibility of failure, SPARK will detect it and allow you to fix it prior to testing, giving 100% confidence that any places it doesn’t complain about are free from these kind of errors.

A Word on Functional Safety

The previous section is interesting because it highlights a fundamental difference between Rust and Ada in terms of how they consider safety. Rust, like many other languages for the IT world, such as Java, C# and C++11, look at software safety through the prism of memory corruption.

The goal of Rust’s memory model, which was the same goal of the Java/C# garbage collectors or C++11 lvalue references, is to provide a mechanism to reduce or avoid memory corruption. This makes a lot of sense, as these languages are used extensively on desktop applications and servers. In such applications, a lot of memory is being employed dynamically and memory corruption is the number one offender in terms of software vulnerability.

On the other hand, SPARK originated from the Ada language and has the roots of its history in high-integrity embedded software. Although memory corruption also plays a role there, the objective of safety is to verify that a given implementation is correct with regard to a given specification.

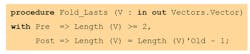

Looking at the above example, we can consider that “the index exists before calling Replace_Element” is part of the specification of Replace_Element and should be respected by any caller. SPARK allows one to specify custom requirements on user subprograms in the forms of preconditions and postconditions. For example, one could write:

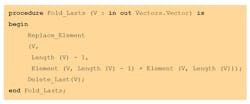

This states that the procedure Fold_Lasts expects a vector of at least two elements and will update the vector so that the length of the new value is one less than the length of the old value. The implementation of the procedure will therefore verify that, given the precondition, the postcondition holds. For example:

This subprogram accesses the last two elements of the vector (which is possible and correct, as we established there are at least two elements) and removes the last one (hence ensuring the length of the returned object is equal to the length of the old object minus one).

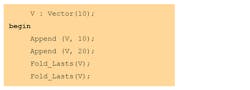

This can then be used in an actual piece of code:

In the above example, the second Fold_Last will issue a proof error, as it should: We’re adding two elements to the vector and folding one leaves only one, which is inconsistent and can be detected statically.

It’s useful to note at this stage that these functional properties, or contracts, have hybrid static and dynamic semantics. In other words, they can be used by the prover, but they may also generate assertions in the final executables to test their validity at run-time. This is particularly useful in cases of contracts too complex to be proven, or while developing contracts to allow for debugging of their behavior at run-time. These contracts can also be used in the non-SPARK parts of the application, which would typically be written in Ada or in C.

Object Orientation

Both Rust and SPARK provide support for object orientation. Beyond syntactic oddities inherited from Ada 95, the SPARK object-orientation model is relatively close to the usual paradigms implemented with C++ or Java. The interesting aspect of the SPARK OO model is that it supports Liskov substitutability analysis. That is, verifying that a class is substitutable by its subclasses in the case of dynamic dispatch. In other words, the child classes must be consistent with their parent.

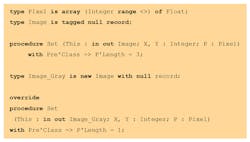

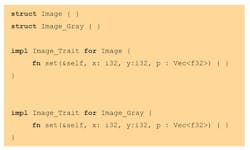

Let’s take a simple example—a class hierarchy that manipulates images. In this design, there’s a root class that can handle an RGB image. We decide to derive from this class to create a specialization that handles grayscale images. Here’s how it might look in SPARK:

This may initially look like a decent OO design However, looking further at the Set method, the “Image” parameter requires a pixel to be an array of three float values, while “Image_Gray” requires a pixel to be an array of one element. On a typical dispatching call from “Image,” the user doesn’t know if Image or Image_Gray is going to be the actual type, and e doesn’t know if the length of a pixel is 1 or 3.

The above is typical of awkward OO designs. SPARK will verify consistency of behaviors declared with methods (expressed in the form of contracts; i.e., preconditions and postconditions) and flag any error. In particular, in the case above, it will complain on the inconsistency of the Set method. One of the general rules is that all inputs accepted by the parent class must also be accepted by the child (and possibly more). For instance, it would be okay for the Set method of “Image_Gray” to accept only a pixel that has one or more elements, which can be expressed as follows in its precondition: P’Length >= 1.

As a side note, SPARK additionally provides static polymorphism, also known as templates or generics, in a model very close to that of C++. The same goes for Rust.

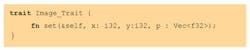

Rust doesn’t provide any means to specify behavior or verify class consistency. However, it offers an OO model that’s much more modern through the notion of “traits.” In Rust, declaring a type Image like the above can’t be done directly in a type, but rather in a trait (a bit like an interface in Java and Ada if you will):

There’s no notion of deriving a type in Rust, so to create an architecture comparable to the above, we would need to implement two different types. Of course, nothing prevents us from having some common type that holds services common to both Image and Image_Gray. But, nonetheless, there are essentially two distinct types implementing the same trait. Such code would look like:

As you can see from the example, a structure isn’t inherently derived from a trait, as it would be in the case of a Java/Ada interface derivation. A given trait is implemented for a given type in a separate block. This gives a nice solution to the known problem of the tyranny of the dominant decomposition that forces a hierarchy of types to be decomposed on one axis only. This also allows third-party trait implementation.

I can use a library in Rust and decide to implement a trait for a type even if that hasn’t been initially planned by the implementer (in particular if the trait is mine!). This is also a nice answer to the problem that was at the origin of aspect-based programming—the separation of concerns—without drifting into overly permissive models such as AspectJ.

What Sets Them Apart

It would take too much time to go over each feature one by one and highlight every single axis that can be used to compare these two languages. We talked a lot about what brings them together and how they look at different angles of similar problems coming up with different solutions. There are, however, interesting elements that also make them very different.

The most visible one relates to specification. Rust doesn’t provide a clear separation between a specification file and an implementation file. As with C or Java, this can be done through language features (you can decide to have traits in a “specification-only” file), but this is left to the discretion of the developer. SPARK enforces a clear distinction between these two notions and provides language-level verification of consistency between specification and implementation.

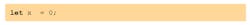

Another aspect is the tradeoff between writability and readability. In Rust, when typing can be statically inferred, it becomes optional. So I can write:

The compiler will know that x is an i32. This becomes particularly useful when the type is actually a complex generic instance, reducing the amount of text to be written. On the other hand, the downside is that it may be more difficult to figure out what the type actually is when reading the code (to the extent that, to date, the Rust documentation mentions types in comments next to variables so that newcomers understand what they refer to).

SPARK takes the opposite stance. It limits to the absolute minimum what’s to be inferred by the compiler, forcing the developer to specify every type precisely at the cost of sometimes pedantic constraints.

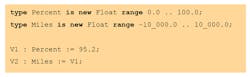

Both languages provide strong static typing features. However, in Rust, native types are just machine types, such as i32, f64, etc. In Ada, a type is a semantic entity associated with constraints that may or may not be defined, such as the range of values or memory size. Moreover, a type is associated with semantics that make it clear that even if it comes down to the same implementation, it should be considered as a different entity. For example:

The compiler will know that V1 assignment into V2 doesn’t make sense because they’re different types. Indeed, miles has nothing to do with percentage, even though they may both end up being implemented as 32-bit-machine floating point. Moreover, extra constraints—here, a range of values—can be verified either statically (ensuring that a value can’t be outside of the range) or dynamically via testing.

Rust provides an extremely powerful and structured macro language that allows one to effectively create expansions of pieces of code based on patterns. There’s nothing similar with SPARK. Rust also provides a so-called “matching” control structure much more powerful than the SPARK equivalent, closer to C/Java switch statements.

Differences do exist in the error recovery model: SPARK has some limited support for exceptions (complete support if you go to the unsafe code mode), while Rust uses a much more constraining notion of “panic” when something is unexpected. Rust supports lambdas and closures, which don’t really have an equivalent in SPARK.

And the list goes on. Determining which set of features is the best is a tradeoff that depends on many different things external to the language, but are instead specific to a given project, team, market, etc. But it’s useful to have some understanding of these differences in order to make an educated choice.

A Word on Ecosystems

Choosing to use one language rather than the other isn’t tied solely to its intrinsic technical merits. A language is the basis of a software ecosystem that includes the availability of additional tools, resources, and support. In this regard, Rust and SPARK are both very similar and very different. They’re similar in the sense that they each rely on an open-source community, though at different levels.

The Rust compiler is LLVM-based, supported by the Mozilla foundation and a large community of hobbyists. The SPARK compiler is GCC-based, and while an open-source community does exist around it, it’s more restricted. The compiler element of the tool is mostly maintained by a software vendor called AdaCore (of which I happen to be part of) and the formal proof engines underneath are maintained and developed in collaboration with various universities.

Both technologies are available for a large set of targets, in particular native and embedded environments (specifically, the obvious: ARM). They’re two open-source strategies, if you will, but shaped very differently.

It would be wrong, however, to consider this picture to be static. With Rust being deployed on a growing number of projects, there’s no reason why commercial entities would not start to provide official support on it. There’s also no reason why professional tools wouldn’t appear for static analysis, code coverage, requirement traceability, code quality, and so on.

On the SPARK side, these tools exist from various vendors, inherited from the Ada history. However, AdaCore has a history of scarce interactions with the communities, limiting its contributions to the production of a few GPL binaries and commits of its compiler sources to the FSF trunk. That facade is also breaking down, with lots of development now done on GitHub and several other community-friendly initiatives being started.

As to industrial usage, the first users of Rust are coming from the IT world (Mozilla needs are definitely IT-related), while SPARK users come from high-integrity embedded A&D applications. Both technologies target embedded application in the more general sense, thinking about things such as medical devices, industrial automation, automotive, and, of course, IoT. So, in a way, they’re two options to address the same needs, perhaps at different levels, perhaps in competition, but perhaps also in symbiosis.

Last but not least, the question of available developers must be considered. There won’t be many people who include Rust in their résumé when getting out of university this year. There won’t be lots of people who include SPARK either. But that’s not really an issue, is it? The language shouldn’t be an obstacle for a decent embedded software engineer, and the internet is filled with tutorials and training resources for both languages.

While this message is sometimes difficult to get through to management, the real question is more about finding these decent embedded software engineers than finding people who happen to claim knowledge in a particular technology. That, however, is an issue on its own, whether you develop embedded application in C, Rust, SPARK, C++, Java, or anything else.

Conclusion

There’s little doubt that Rust has a bright future ahead of it. It provides a unique approach to software reliability and safety, and is being adopted by a growing number of projects. The language seems to address reliability concerns in a much better way than C or C++, without the overhead of VM-based languages like C# or Java. It’s a young language, and some features or tools may still be missing, but there’s no reason why that shouldn't be overcome in the future.

There’s little doubt SPARK has a bright future ahead of it, too. It provides a unique approach to software reliability and safety, and is being adopted by a growing number of projects. The language leverages its Ada foundation to target a large set of use cases in the embedded domain. SPARK is also a relatively young language (at least in its current form), and the language is rapidly evolving. At the time of this writing, for example, new prover capabilities are being developed and new containers are being written.

It seems that the two languages can coexist. SPARK remains very well-suited for safety-critical embedded applications, while Rust looks like a good fit for the IT domain. Generic embedded applications may lean on one side or the other, depending on various factors. Both languages bring interesting ideas to the table—and both suffer from shortcomings. Perhaps there’s room for cross-fertilization.

Above all, it’s very nice to see new languages considering safety and reliability at their core. The market can only be enriched by a larger offer of technologies, which will undoubtedly push better practices in industrial settings. As a matter of fact, I’m not sure if I care so much whether you’re using SPARK, Rust, or a super-constrained MISRA-C—as long as my car, my money, and my blood pressure are handled with safe and robust pieces of software!

Read more article from the Ada and SPARK series in the Embedded Software section of our Series Library and check out the TechXchange on Rusty Programming.