“The principle that governments should mandate ISPs to treat all data on the Internet the same, and not discriminate or charge differently by user, content, website, platform, application, type of attached equipment, or method of communication.”

This is the formal definition given to network neutrality. But not all people may look at it the same way. People from diverse backgrounds could disagree on whether it’s congenial to the consumer or to the internet service provider. Differing opinions may arise from differing ways net neutrality is understood. In this article, I provide my own interpretations and perspectives on the matter.

The debate is whether net neutrality should be rescinded by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the governing body for America’s telecommunication services. People argue that net neutrality is keeping greedy corporations at bay from exploiting and abusing the internet service they provide. A common cited example would be the throttle of traffic from opulent hosts and concurrent impediment from their competitors at a premium.

Voices from the other side, those who tend to slip into a hole of internet infamy (take FCC’s director, who earned heaping loads of flak), counter a more alluring market for ISPs as the suffocating grip from the plethora of rules and regulations are relaxed.

But, who’s right? Whose side carries more weight? It’s clear both the “Yes” and “No” sides have their corresponding pros and cons.

A Look at Both Perspectives

I think this “who’s right” question can’t afford a straightforward answer. But if some goblin were to pop out of nowhere and ask me from out of the blue (without giving me any time for forethought), I’d have to say no. There aren’t any clear proofs or salient points that succinctly correlate preexisting FCC regulations and an ISP operating in the red. However, if the time comes when there’s a scarcity of ISPs (which I doubt will occur in the near future), then the FCC must repeal its laws on network neutrality.

In addition, a closer look at the argument of a more enticing market gives too much priority on the ISP side. I know it shouldn’t be a monopoly or duopoly, but I believe it also shouldn’t be as pervasive and competitive as fast foods or consumer appliances. Providing too much leeway for ISP startups can be disruptive and pernicious to the economy in the long run.

Then again, my answer can shift from negative to positive if only a number of regulations are withdrawn based on certain criteria (and not all).

Thought experiments, made popular by Albert Einstein, and a favored pastime of mine when I’m waiting in line at a Subway or soporific in daily commute, may be used for this case. Let’s say web content provider “A” promotes videos and web content provider “B” promotes articles/files. “A” and “B” deal with commercial products that are similar in nature and both are connected to the internet through ISP “X.” Now, let’s say “A” is audaciously depraved enough to bribe ISP “X,” offering $8 million for throttling its traffic.

After some time, “B” notices its traffic is getting slower (by internet connection self-tests) and decides to shift to ISP “Y.” “A” then has to bribe ISP “Y,” too. Now, since net neutrality is repealed, entering the ISP market is too much of a breeze. “B” can keep shifting ISPs with ease, and “A” will keep risking bribing ISPs until it gets caught (not to mention the lengthy and tedious steps one needs to take to establish a bribe).

Digging Deeper

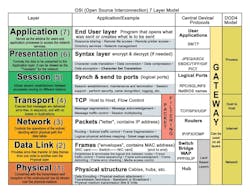

The previous paragraphs dealt with the application layer of the OSI model. What about the lower layers? The network, data-link, and physical layers?

The figure depicts the well-known 7-layer OSI model. When talking of net neutrality and which rules to repeal, it’s worth considering the impact this model will have on the FCC’s decision-making process.

Well, the network layer is pretty much defined by IPv4 and IPv6, differing mostly on what protocol is employed to manipulate them in a network, whether it’s a routing protocol, distance vector protocol, or link-state protocol. A unique host can be assigned a unique IP address, but manipulating the way it’s routed at the gateway beyond is challenging. In fact, any modification applied to this layer below will not only slow down one IP address, it will slow down all of them due to the significant addition of rules to the routing table.

Now, it’s not just the ISPs that are being constricted by too many rules, it’s the switches and routers as well.

How about the physical layer? We then find a problem with the definition in the first paragraph. If net neutrality really stood for what it meant, note—“to not charge differently by type of attached equipment or method of communication”—then why is fiber-optic internet/100Base-FX more expensive than the copper-wire/100Base-TX internet?

I may not be able to feature all loopholes encompassing this delicate topic. But, as long as these statements aren’t addressed, I will remain reproachful of net neutrality’s demise.