Download this article as a .PDF

BMW and Audi, who often pioneer much that is new in automotive electronics globally, are in the process of developing radically new electronics architectures for future vehicles. The carmakers are taking a similar approach: high-performance central computing units replacing today’s outmoded distributed computing architecture.

The auto industry is facing profound disruption, with new competitors from the IT and consumer electronics worlds making inroads. Google, Apple, Tencent, Uber, Alibaba, and Baidu are developing revolutionary new mobility solutions. Tesla is already here. Automated driving is coming faster than initially thought. The vehicle’s interior is quickly going digital.

A revolutionary new architecture is needed that can take advantage of what has become the state of the art in consumer electronics: internet connectivity, cloud computing, swarm intelligence, and over-the-air feature updates.

Today carmakers purchase infotainment systems and vehicle control systems from tier-one suppliers who tightly embed software components within electronic control units. If a carmaker wants to change suppliers, it must validate and test a completely different software stack—an enormously time-consuming and expensive endeavor.

Thomas Mueller, Audi’s new top electrical and electronics engineer, wants automotive systems to be as mature in terms of hardware decoupling as IT systems have been for decades. In a conversation earlier this year, Mueller outlined his vision for a new vehicle architecture, which he expects to realize major elements of by the start of the next decade. “There might be one, or a few, central computers,” he said. “We haven’t decided yet. In order to decouple hardware from software we need a standard operating system like Linux, standard Ethernet connections, standard I/O ports and so on.”

Mueller noted that the introduction of Unix more than 40 years ago in the IT industry allowed data center operators to source their application software from different suppliers. “They were no longer stuck with a monolithic supplier responsible for both the software and the hardware,” he explained. “Software from suppliers A and B could run on hardware from suppliers X and Y…So in my vision you could think of the car of the future as a data center on wheels.”

BMW and Audi are developing end-to-end architectures that connect wirelessly from the vehicle’s onboard electronics to the carmaker’s back end, and from there to HERE’s back end in the cloud, via the internet (see the Audi block diagram below). HERE, the digital map company jointly purchased by BMW, Audi and Mercedes-Benz, will use crowdsourced data to provide precision maps suitable for autonomous driving and location-based services.

Benefits to Carmakers of Separating Software and Hardware Development

- Flexibility: OEs can more easily switch suppliers and update vehicles with new features after sale.

- Far easier to develop software on known, standard operating systems/hardware platforms

- Faster deployment by eliminating redundant validation and testing of reused software

- Quicker deployment of diverse implementations of functionalities—e.g., fault-tolerant versions

- Improved engineering productivity

- Minimized risk of bringing updated features to market

- Proven application software can be reused

Obstacles

- Suppliers fear losing business

- Lack of standard interfaces for hardware

- Added cost of computing headroom

- Need to better understand hardware virtualization

- Carmakers’ typical domain-oriented engineering organizations

- Most supplier roadmaps don’t yet comprehend hardware-software separation

- Standard operating system for central computers is needed

Similar End-to-End Architectures

What’s most distinguishing about the new vehicle architecture is what Audi refers to as its central computing cluster and what BMW calls its central computing platform. Both consist of one or more general-purpose, high performance computers powered by extremely capable processors from suppliers such as Nvidia, Qualcomm (Snapdragon), or Mobileye. The car’s functions will increasingly depend on broadband data communications within the vehicle and with the cloud.

Carmakers who serve high-volume, non-premium vehicle segments might think the central computing architecture is not for them, or at least something that can be deferred until much later. But according to Ricky Hudi, who preceded Mueller as Audi’s top E/E, “scalability was a major requirement for the architecture. The entire VW Group should be able to benefit from it.”

Audi’s End-2-End Architecture

One motivation for this radical architectural departure is complexity reduction. Today, much of the vehicle’s functionality comes from the exchange of signals between ECUs. “Already at BMW we must deal with 12,000 signals that are sent and received to build these connected functions,” said Kai Barbehön, BMW’s vice president of product offering, E/E software architecture, and platform management. “But we are moving to highly automated systems. The back end comes into the system providing dynamic information. And we need more sensors for doing highly automated driving functions. We will not manage the complexity that arises from these new functions if we do not change our electronic architecture.”

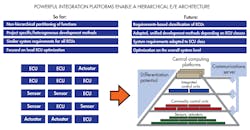

At the top of BMW’s forthcoming hierarchical software architecture will be the central computing platforms for vehicle domains such as infotainment, autonomous driving, and body control, including a communications server that links the central platform with electronic control units, sensors, and actuators (see figure below).

Next down in the hierarchy are the integrated electronics control units, standard ECUs similar to those used today for electronic stability control or engine control, in which OEM-specific functions are integrated.

Further down the hierarchy are commodity control units, off-the-shelf parts with a range of standard functionalities (such as window lift or other body control functions). These standard ECUs will be free of any carmaker-specific functions or software code.

Barbehön wants a single software platform that is common to all the central computers. He envisions, possibly by 2025, a single Linux-based platform that melds a safety-critical Autosar Adaptive autonomous driving platform with BMW’s Genivi infotainment platform. “Autonomous driving comes with demanding requirements for safety and security,” Barbehön said. “Infotainment is not very demanding on safety, but very demanding on security. If you list all the requirements, there is a chance that they can be met with a single software platform that can be configured for both domains.”

The architecture’s main benefit, said Barbehön, is a significant reduction in the amount of software that must be developed and validated. “With a stable platform that is owned, managed and maintained by us,” he noted, “we get to reuse the basic platform software, and we know that the applications we have already tested are going to work in the next ECU, even if it is from a different supplier. Of course we will still have to conduct final tests.”

Software-hardware decoupling is already happening in the infotainment domain. Some head units are able to accommodate software such as navigation from best-in-class, third-party suppliers, who offer the application as a part. “This approach must now move into other domains,” suggested Mueller. “The big question is, can we find suppliers who will be ready to supply what we need when the time comes?”

Like this article? For more deep analysis of electronics technology and business trends in the global auto industry, subscribe to the Hansen Report.