MEMS Micromirror Chipset Drives Steerable Auto Headlights

The pivoting, self-steering headlight of Preston Tucker’s legendary 1948 car (only 51 were built) may be coming back, but using a very different technology. Unlike the mechanical linkage his Tucker Torpedo used, Texas Instruments has announced a MEMS-based approach using its proprietary digital light projector (DLP) technology (Fig. 1). This is yet another example of MEMS technology being applied to many diverse roles in the vehicle, a trend which started with airbag impact sensors, expanded to accelerometers for rollover detection, and now is used in gyroscopes and accelerometers for navigation IMUs (inertial measurement units).

Introduced at CES, TI’s DLP5531-Q1 DLP chipset for steerable headlight systems offers full programmability along with high resolution of more than one million addressable pixels per headlight—a figure which exceeds the resolution of existing adaptive driving beam (ADB) technologies by more than four orders of magnitude. It is targeted at enabling headlight systems that maximize brightness for drivers on the road while minimizing the glare to oncoming traffic or reflections from retroreflective traffic signs. Further, as a passive reflecting-mirror approach, it can be used with any light source, including LED and laser illumination, thus giving engineers a way to more precisely control light distribution on the road with customizable beam patterns.

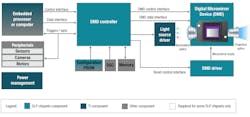

DLP technology, introduced in 1996, consists of an array of highly reflective aluminum micromirrors forming a digital micromirror device (DMD); each such device contains up to 8 million individually controlled micromirrors built on top of an associated CMOS memory cell. This electrical-input, optical-output MEMS device is used as a high-speed, efficient, and reliable spatial light modulator. The micromirrors are individually tilted via electrostatic deflection to steer imping light, transitioning between hard stops at two angles of either ±12° or ±17°, depending on the selected DMD. The switching rate of the micromirrors can range up to 10,000 times per second. A complete chipset consists of the DMD, driver, support circuitry, and processor (Fig. 2).

The use of DLP technology for automobile adaptive driving beam implementations is yet another example of an innovation finding new applications, often acting as a building block beyond the original intention, as explained dramatically in James Burke’s insightful and thought-provoking, still-relevant 1978 TV series and book Connections. DLP was originally envisioned as the core of a video-projection technology and is now used for both large-size theater systems and handheld picoprojectors; it is also being designed into heads-up displays (HUDs), as well as in vehicles and aircraft, 3D printers, and even scientific instruments such as spectrometers.

However, adaptive driving beam designs were not at the top-tier original applications list, yet DLP is proving to be an attractive solution to this application challenge, which also requires that components meet the stringent automotive standards for operation despite harsh temperature, vibration, electrical transients, and other conditions. TI says that lead customers are already sampling and designing with the DLP5531-Q1 chipset for high-resolution headlight systems. The chipset will be more broadly available in the second half of 2018.

About the Author

Bill Schweber

Contributing Editor

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple topic-specific sites for EE Times, as well as both the Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN.

At Analog Devices Inc., Bill was in marketing communications (public relations). As a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these.

Prior to the MarCom role at Analog, Bill was associate editor of their respected technical journal and worked in their product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls.

Bill has an MSEE (Univ. of Mass) and BSEE (Columbia Univ.), is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.