South Korean Regulator Adds $853 Million to Qualcomm's Antitrust Fines

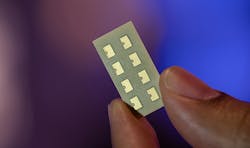

Qualcomm, the world’s largest maker of mobile chips, sewed its success on a bed of patents. But as the company has signed global licensing deals for those patents, which contain industry standards for 3G and 4G cellular communications, it has come under increasing scrutiny.

In 2015, China’s top antitrust regulator forced the chip maker to pay almost a billion dollars in fines and take a smaller cut of devices sold using its patents. In Europe, officials have accused it of giving kickbacks to a smartphone maker that only used its modems. The San Diego company is also fighting legal battles over its royalty model in South Korea and Taiwan.

Now, its domination of patents is again in regulatory crosshairs. Last week, South Korean regulators hit Qualcomm with an $853 million fine for alleged antitrust violations. Officials ruled that the company has abused its dominant market position to cut unfair and overly-broad licensing deals. It was also accused of hoarding wireless patents from rivals that wanted to pay for them.

After a three-year investigation, the Korea Fair Trade Commission ruled that Qualcomm hindered competition by withholding critical patents from rivals like Samsung and Intel. That restricted their sales and left them open to patent lawsuits, the agency said. In a report released last week, the regulator also said that Qualcomm had refused to sell chips to phone makers that didn’t agree to a separate licensing deal for its blueprints.

Qualcomm, calling the decision “unprecedented and insupportable,” rejected the idea that it hampered other chip suppliers. The company argued that licensing patents has been an critical part of the semiconductor industry for decades. Those practices are also widespread in South Korea, which has not questioned the practice until recently, the company said.

“Qualcomm strongly believes that the KFTC findings are inconsistent with the facts, disregard the economic realities of the marketplace, and misapply fundamental tenets of competition law,” said Don Rosenberg, Qualcomm’s executive vice president and general counsel, in a statement.

Qualcomm plans to appeal the decision, which could have consequences on how it does business with phone makers. But like Qualcomm's other legal fights, the lawsuit could take years to play out.

Any change to how Qualcomm handles licensing patents could create big ripples in its bottom line. The company splits its business between making chips and licensing patents to phone manufacturers. In 2016, the licensing deals brought about a third of its $23 billion in total revenue. The profits are funneled back into research for next-generation products, like 5G modem chips, Rosenberg said.

Qualcomm, which also sells the main processors inside smartphones, charges patent royalties based on the wholesale price of the smartphone. It is usually just a few percent of every sale. Less than 3% of its licensing revenue came from royalties from Korean phone makers, the company said.

South Korean investigators ordered Qualcomm to negotiate new contracts “in good faith” with existing customers that sell smartphones in South Korea. That could directly result in better licensing deals for South Korean companies like Samsung and LG, but it could also affect how it deals with customers like Huawei and Apple.

But more importantly, the regulator also ordered the chip maker to start licensing patents to rival chip makers like Samsung and Intel, which has only recently cracked the code on selling its modem chips to phone makers. Qualcomm typically doesn't share its technology with them.

The orders went further than Qualcomm’s settlement with the Chinese government in 2015. The regulators imposed a $975 million penalty and forced Qualcomm to accept a lower rate on phones sold in the country. But the decision didn't force the company to change its licensing model. It actually helped to stabilize its standing in the world’s largest smartphone market, where it had struggled to collect royalties from Chinese firms.

The investigation itself has been incubating for years. It started in August 2014 after the South Korean commission received complaints from industry insiders. Qualcomm has closely followed the case, making in January what some legal experts called an aggressive move to obtain documents that Apple, Intel, and other companies gave to investigators.

In its decision, the South Korean officials said Qualcomm’s royalty model is unfair because companies must buy licenses for Qualcomm’s entire patent portfolio, even ones they don’t need. Their report also contends that Qualcomm used its chip supply as leverage to coerce smartphone makers to also strike patent deals.

“It is a structure under which handset companies have to bite the bullet and accept Qualcomm’s license terms, even if they are unfair, because if the modem chipset supply is suspended, handset companies would face the risk of their entire business shutting down,” the regulator wrote in its report.

South Korea's ruling is only the latest challenge to Qualcomm's licensing business.

It builds on another suit that the same regulators brought against Qualcomm in 2012. They fined the chip maker around $225 million for offering rebates to phone makers who buy products mainly from Qualcomm. The ruling also said that the company charged higher royalty rates to phone makers that buy chips from competitors. That case is under appeal with the Korean Supreme Court.

The company has also run afoul of antitrust rules in Europe. Last December, Europe’s Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager – who has increasingly sparred with American tech companies like Google and Apple – sent antitrust objections to Qualcomm. She said that it had priced chips below cost to crush Icera, a smaller competitor now owned by Nvidia. In another case, she said that it had thrown rebates to an unidentified phone maker in return for using its chips exclusively.

This latest ruling does not go into effect until the regulator sends a written order to Qualcomm, and that could take around four to six months. Then, it would have to pay the fine. If the chip maker wins the appeal, it could get a partial or full refund.