Technology Giants to Step Up Chip Design Ambitions in 2022

This article is part of the 2022 Electronic Design Forecast issue

Some of the world’s largest technology firms are shunning standard chips in favor of designing them in-house, a move that is roiling the semiconductor industry and shifting the balance of power in the sector.

Now Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft, Tesla, and other Silicon Valley titans are taking things to the next level in a bid to build chips with improved performance, power efficiency, and cost. The push into custom chips is a mounting threat to industry giants such as Intel, AMD, Qualcomm, and others and it has forced chip firms to respond by rolling out silicon specifically designed for customers' needs in areas such as AI.

While tech giants revealed a wide range of custom chips for data centers and consumer devices in 2021, they are set to step up their ambitions again in 2021, taking control of even more aspects of chip design.

Apple is in the final year of swapping out the Intel chips in its Mac laptops and desktops in favor of its own in-house processors, modeled on its high-end A-series chips at the heart of its flagship iPhones and iPads.

The plan fits into the technology giant's broader strategy of replacing many third-party parts with bespoke chips, a strategy that springs from Apple's philosophy that owning key technologies is a major advantage over rivals. Brady Wang, a semiconductor analyst at Counterpoint Research, said the use of custom chips eases its dependence on a single supplier and helps it roll out unique, differentiated features in its devices.

Wang said that Apple's investment in custom chips gives it more control over future releases of its iPhone, Macs, and other hardware and a higher grip on the ecosystem building software and apps for its products.

The likes of Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, and others are increasingly taking pages from Apple's playbook, replacing off-the-shelf server chips from Intel in favor of in-house chips tailored for their needs.

On top of that, the custom chip-making race comes during an ongoing global chip shortage that's raising costs across the supply chain. The supply chain challenges are pushing companies to reconsider where they buy chips.

“Apple Inside”

Apple was an early mover in the world of in-house chip development, releasing the first generation of its Arm A-series systems-on-a-chip (SoCs) for the iPhone more than a decade ago. Apple has improved the mobile chips and the central processing units (CPUs) inside to the point where they can rival Intel's chips for PCs.

In recent years, Apple has targeted its chip-making prowess at the iPad and other gadgets in its lineup, such as its Apple Watch and AirPods wireless headphones, to roll out features that stand out from rivals'.

For Apple, the strategy gives it control over a more complete package of technology in its iPhones, iPads, Macs, and other consumer gear, ranging from software and the operating system to the system hardware and silicon inside. Building more of the silicon and sensors that it previously outsourced has helped Apple stand out because it can plan how the chips work together to cut power and ramp up processing speeds.

Apple’s chip-making ambitions have reshaped the hierarchy of the semiconductor industry, analysts said.

Its success with the A-series processors in the iPhone has pushed it to the front of the line for the world's most advanced process technology from TSMC, even placing it ahead of the likes of Qualcomm and AMD.

But it's taking things to another level with its M1 processors for Macs. In 2020, Apple announced it was moving away from Intel’s products in favor of its in-house "Apple Silicon" chips, including the M1 chip that now sits in the latest iMacs and iPads. Apple announced plans to phase these chips into its desktop and laptops in a two-year period, ousting the Intel chips used in Apple's PCs for the last decade and a half.

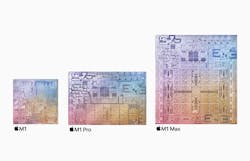

The M1 stunned the semiconductor industry with its combination of performance and high levels of energy efficiency. These attributes stem from the tighter integration between Apple's silicon, hardware, and software. Apple is upping the ante with the 5-nm M1 Pro and M1 Max used in its MacBook Pros, which have what it calls “unparalleled” performance for video editors, photographers, and other "pros."

Unless its chip division faces delays, 2022 is the year Apple completely pushes Intel out of its Mac lineup, even ousting it from the top-of-the-line Mac Pro desktop, which currently runs on Intel’s Xeon server CPUs.

Silicon Powerhouse

Part of the calculus for Apple is economics. The consumer electronics giant can handle the engineering costs of in-house chips because of the savings that result from simplifying its supply chain. Instead of paying Intel, Qualcomm, or another semiconductor firm to design a chip and then get it manufactured, Apple can develop the chips itself and work directly with its foundry partners to contract out production.

Thus, the technology giant can pass the savings on to customers or shareholders, industry analysts said.

Apple’s chip department has blossomed in recent years to what is reportedly thousands of engineers, bolstered by its deal to buy PA Semi over a decade ago. Leading the effort is Johny Srouji, the head of hardware technologies, who has become one of the core members of Apple’s executive team during its campaign for custom silicon. He helps chart out the features in future Apple’s chips years ahead of time.

Over the years, it also worked closely with many of its chip vendors to get semi-custom parts made for its products. Many of the firms responded by building out whole divisions specifically devoted to Apple chips.

To back up its "in-sourcing" strategy, Apple is opening offices and hiring chip designers in areas such as cellular modems from suppliers such as Qualcomm in San Diego, California, and Intel in Portland, Oregon.

Over the last decade, the company has expanded its exploits in custom chip development, building a wide range of components for its consumer gear such as power management ICs and Bluetooth ICs as well as more of the modules inside its SoCs, such as the graphics processing unit (GPU) and memory controllers. It has also created many of the advanced sensors and the haptic engine in its phones and other gadgets.

Apple will likely take its semiconductor ambitions to new levels in the future. The company is reportedly readying its first 5G baseband modem, a vital iPhone component that it currently buys from Qualcomm.

Take to the Clouds

Apple’s accomplishments in chip-making have been a revelation for other technology firms fighting over the cloud computing market and pursuing dominance in other fields, such as artificial intelligence (AI).

Amazon, Google, and Microsoft are moving deeper into chip design to wring more performance out of the millions of servers spread out in globe-spanning networks of data centers, which they use not only internally but also rent out to outside firms over the cloud. Even small improvements in performance or cuts in the cost of powering and cooling chips in servers add up in the context of their vast operations.

Google and other technology giants continued to rely on third-party components for years while amassing the engineering depth and gaining the expertise they needed to design chips and other parts themselves.

But as they did so, they also pushed suppliers to incorporate custom features into the parts they needed.

Intel has said in the past that around 60% of its server processors sold to companies that run vast data centers are customized to a customer's needs, usually by disabling features of the chip they don't need.

Google was an early mover in the cloud sector, releasing its first custom chip called the Tensor Processing Unit (TPU) as a way of slashing costs and improving the efficiency of artificial intelligence (AI) chores in its data centers starting in 2016. In 2018, the company said it would allow other companies to buy access to those chips through its cloud service in a shot against NVIDIA. It's currently on its fourth-generation TPU.

Microsoft, the No. 2 player in the cloud industry behind Amazon, has also invested in chip designs for data centers, including a class of programmable chips based on Intel FPGAs to run artificial intelligence tasks.

Amazon has designed a wide range of networking chips and other processors for its cloud-computing arm, called AWS, including a family of server CPUs called Graviton based on blueprints from Arm. It has upgraded the Graviton CPUs every year since it rolled out the first generation in 2018. Last year, it rolled out Graviton3 with over 50 billion transistors crammed in 64 cores and support for DDR5 and PCIe Gen 5.

AWS has said that it has moved into making its own processors given the performance gains it would see by stripping out the unnecessary features in Intel’s Xeon server processors that dominate the data center.

According to AWS, cloud-computing services based on its in-house Arm server CPUs cost significantly less than others that depend on Intel’s Xeon chips because of the gains in energy efficiency and speed.

Amazon rolled out another server chip that it calls Trainium, which is designed to train machine learning models and is set to battle against NVIDIA GPUs. The chip should be available to its customers by early 2022. The cloud vendor said it would run training up to 40% more cheaply than Nvidia's flagship GPUs. It also announced its second-generation chip for carrying out AI software after it's trained, called Inferentia.

Amazon’s chip-making endeavors started taking shape after buying chip startup Annapurna Labs in 2015.

Tesla is also throwing its weight behind server chip development: The electric-vehicle firm announced last year that it is building out a processor called the “D1” and a computer system called “Dojo” based on it for use in data centers to help train the artificial intelligence models behind the self-driving mode in its cars.

Custom Silicon Surge

As Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and other technology firms take on Apple’s dominance in the consumer electronics markets, they are also expanding their chip-making ambitions to close the gap with Apple's.

Google rolled out its latest Pixel 6 smartphone with a custom processor called Tensor that integrates the core processing modules in the phone, including the CPU, GPU, and other intellectual property (IP) blocks.

Rick Osterloh, Google’s senior vice president of hardware, said Tensor gives it the computing resources it needs to roll out advanced features in areas such as image processing it hopes will set its products apart. The chip, which is specifically designed to assist with artificial intelligence tasks, takes over the slot held by Qualcomm’s Snapdragon chips in every generation of the Pixel, which the company rolled out in 2016.

Google is reportedly getting closer to rolling out in-house CPUs for its Chromebook laptops. The company allegedly plans to use its chips in laptops and tablets that run its Chrome operating system by 2023 or so.

But at this stage, not every technology firm is looking to handle all aspects of chip design by themselves.

Microsoft currently uses Intel-based processors for the majority of its Surface line of laptops. But in recent years it has partnered with Qualcomm to design the Arm-based processor at the heart of its Surface Pro X laptop. Qualcomm has also partnered with Microsoft to develop a mobile chip from the ground up to run battery-powered, ultra-light augmented reality (AR) headsets for use by both consumers and businesses.

But the software giant is no stranger to semiconductor development. Microsoft is reportedly developing a central processor for servers it rents out over the cloud and possibly for Surface devices in the future, too.

The software giant rolled out a new generation of the electronic pen that pairs with its Surface laptops last year. A custom chip inside called the "G6" is used to restore some of the physical sensations that are lost when writing or drawing on a display. The chip is used to create vibrations to mimic the feel of a pen on paper such as when users scribble through a word to delete it or circle a phrase to select or highlight it.

Power Shift

The scale of the technology firms bringing chip design in-house presents a challenge for chip companies. Their customers have the financial firepower to bypass them completely and build the chips themselves.

NVIDIA, the largest US semiconductor firm by market cap, is valued at about $695 billion. Intel is at $226 billion. Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google-parent Alphabet each top $1.5 trillion in market valuation.

Microsoft is also persuading partners in the chip sector to put its intellectual property in their products.

Microsoft has rolled out an ultra-secure co-processor called Pluton that will go in future computer chips for PCs, including its Surface laptops. The Microsoft-designed module can block the theft of secret keys used in cryptography or other information by locking it within a secure zone in the CPU. Pluton promises to add another layer of hardware and software protection against hackers trying to get inside the system.

Intel, AMD, and Qualcomm plan to incorporate the ultra-secure Pluton security module into future CPUs for PCs that run the Windows operating system. Microsoft introduced Pluton in 2018 as part of its Azure Sphere IoT service, working with chip firms to build it into microcontrollers for Internet of Things devices.

AMD plans to ship the first x86 processor for PCs with Pluton inside in early 2022.

Serious Competition

In the end, Amazon and other Silicon Valley titans have said they want to boost competition in the chip sector by offering more choices and, in the process, push semiconductor vendors to step up their game.

It is unclear what it would take at this point for Apple, Amazon, or other technology giants to return to off-the-shelf, third-party chips. Even so, chip firms need to take the competition seriously over the long term.

For Intel, Qualcomm, and other chip giants, 2022 will be another year of trying to prove customers wrong.

Read more articles in the 2022 Electronic Design Forecast issue