Nvidia’s Quadratic Processor: The NV1

This article is part of the Electronics History series: The Graphics Chip Chronicles.

Founded in early 1993, Nvidia set out to revolutionize the PC and console gaming market with 3D graphics technology. They succeeded beyond anyone’s wildest imagination but not without suffering some bumps and bruises in the process. It just made them smarter and stronger.

Nvidia announced itself in the summer of 1994. It planned to develop single-chip media accelerators for high-quality interactive multimedia on PCs.

“We intend to focus our engineering resources on the rapid development and introduction of new families of industry-defining Media Accelerators,” said president and co-founder Jensen Huang. Nvidia said that its first-generation Media Accelerator would enable PC platforms to deliver high-performance 2D and 3D graphics, video, a digital joystick interface, and advanced audio capabilities to accelerate the rapidly growing installed base of multimedia applications.

The premise was to build a 3D graphics controller based on quadratic texture mapping. Quadratic rendering was a dramatically different approach to the polygon rendering that prevailed at the time.

The company was also seeking to differentiate itself by incorporating audio capabilities in the chip. If it succeeded, gamers would only have to purchase a single add-in board (AIB).

Nvidia followed the fabless model. However, it was not easy for a startup to grab a foundry’s attention and, more importantly, commitment. Setting up a production line was (and still is) a risky and tricky proposition. Nvidia lucked out and convinced SGS-Thomson Microelectronics (SGS) to build the first-generation multimedia chip, and in exchange, SGS would market it.

SGS and Nvidia rolled out two versions of the NV1 multimedia accelerator. They said the chips were the first multimedia accelerators to deliver real-time photorealistic 3D graphics on the same die.

Nvidia marketed the NV1 VRAM version, while SGS offered the STG2000, the DRAM version. Introduced in May 1995, the STG2000 was a PCI-based multimedia PCI AIB. Nvidia also secured a design win with Diamond, the largest AIB supplier at the time. Diamond then introduced the Diamond Edge 3D to retailers.

But Nvidia, Diamond, and SGS struggled to get game developers to invest in the NV1’s quadratic texture mapping technology and Nvidia’s accompanying software development kit (SDK).

The first video game company to show interest in Nvidia’s chip was Sega, which was looking to bring the games available on its Sega Saturn to PCs. Saga’s interest prompted Nvidia to include a joypad port in the chip.

The Nvidia NV1

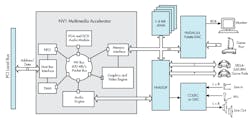

The NV1 chip was the PC industry’s first single-chip accelerator supporting the multimedia features of Windows 95. The features included 2D/GUI acceleration, real-time texture-mapped 3D acceleration, wavetable audio acceleration, full-motion video acceleration, and digital input acceleration. The NVI also supported legacy applications with multimedia drivers for Windows 3.11 and integrated VGA for DOS.

The key features of the NV1:

- Single-chip multimedia accelerator

- Support for industry standards

- Acceleration for all DirectX API’s under Windows 95

- Industry-leading GUI acceleration

- Full-motion video acceleration (Indeo, MPEG, Cinepak)

- Real-time texture-mapped 3D graphics

- Acceleration of all 3D standards: triangles, quadrilaterals, and curves

- Hardware audio wavetable synthesis

- Enhanced digital game port

- System-level performance and cost optimization

Around 200,000 of the approximately 250,000 transistors in the NV1 were devoted to the chip's purely graphical (2D and 3D) portions.

The first LSI graphics accelerator chips came to market in the early 1980s as 2D drawing engines with CAD as the primary application. In 1981, SGI introduced the first 3D transform engine, the Geometry engine. In 1997, Matrox became the first company to offer a 3D AIB with the SM 640 based on the SGI Geometry Engine.

The first 3D graphics chip was the Yamaha YGY611. However, it was not fully integrated, lacking VGA and perspective capabilities. The first completely integrated 2D/3D chip was Nvidia's NV1, which supported VGA, translation, plus video and audio capabilities.

The chip was the earliest example of accelerated computing, making the peripherals the accelerators. A virtualized programming interface allowed hardware to change while software (the programming architecture) continued to work. Nvidia’s strategy is the same today, tracing its roots to the early days of the company.

Nvidia co-founder Curtis Priem and Chief Scientist David Rosenthal were the chief architects of the chip and its programming model, and another co-founder Chris Malachowsky was the chief engineer. The company’s goals went beyond the NV1. Nvidia was looking to create a virtualized architecture for things I/O (including graphics and audio that it could build on into the future.

As a result, Nvidia’s SDK was very object-oriented. A developer would open a class type (graphics, streaming, or audio) and then write directly to the class type’s registers in the targeted chip. If the chip supported the class and those registers, the operation would be executed in the chip’s hardware. If not, a privileged software kernel would be called by the chip (unbeknownst to the developer) that would execute the operation on the host, often with support from the chip’s hardware. As far as the developer was aware, the targeted chip supported everything exposed in the SDK.

Before Microsoft introduced DirectX, Nvidia envisioned game developers would write to the SDK for their application’s acceleration.

The same approach is at the heart of Nvidia’s designs today, allowing the company to reuse large swathes of code between generations of its graphics processors. The company’s strategy is most clearly displayed in its drivers and the new platforms created with it – CUDA and Deepsteam, for instance.

Nvidia said that its goal was a multimedia architecture that would address the well-known problem with multimedia PCs of the time. The PC of that era was not so much a platform as a collection of single-function add-ons that made life difficult for both developers and consumers. Nvidia claimed its architecture provided a “coherent multimedia platform” with concurrent media streaming, interactive 3D graphics, high-fidelity audio synthesis, full-motion video texturing, and a digital joystick.

The Sega Deal

The big win, PR-wise, was its partnership with Sega. Sega of America established an exclusive licensing agreement with Nvidia and said it would convert Sega’s Saturn and arcade software to CD-ROMs for PCs equipped with Nvidia’s multimedia accelerators. Nvidia set up an exclusive license for PC 3D accelerator AIBs, meaning that Saturn-based games could not be ported to any other 3D PC AIB hardware.

That software pushed Sega Saturn’s sales to more than one million units in Japan in the wake of its release in November 1994. Launched in the U.S. in May 1995, the Sega Saturn quickly sold out of its limited initial U.S. distribution. The company said it would be in full distribution by early September. Saturn games were set to be released for Nvidia-based products three to six months after appearing for the Saturn console.

Tom Kalinske, president and CEO of Sega’s US division, said at the time that he believed the markets for gaming PCs and game consoles such as the Sega Saturn would thrive in the future. The PC games market could reach approximately 20% to 25% of the video game market by 1990, he estimated. Sega said it would spend $30 million to $50 million on advertising for Saturn over the next year.

According to Nvidia, Sega’s software would take advantage of every facet of the NV1 processor, driving the chip to its limit. Huang, Nvidia’s CEO, believed that “PC consumers are going to be stunned with the results of our combined efforts.”

Intel also entered the picture and planned a presentation at SIGGRAPH with Nvidia. Intel said it would also make Sonic the Hedgehog available to OEMs (Intel ported it using its native signal processing software, or NSP. That effort later resulted in a fight with Microsoft that got to the U.S. Department of Justice (but that’s a story for another time).

The Sega deal was a significant coup for Nvidia. The company’s quad-patch approach had some industry analysts wondering if it was too radical a departure from conventional tri-meshes to get developers on board.

Conclusion

But Nvidia was too far ahead of the curve, as it turned out. The PC industry ended up staying with polygonal graphics. There were criticisms of Nvidia’s approach, including the assertion that 2D graphics performance could not compete with other options at the time, particularly in DOS. The NV1’s audio quality failed to live up to expectations, and the AIB was expensive. The result? It failed to gain ground in the market.

Nvidia co-developed the NV2 with Sega for use in the Dreamcast console. But Sega ended up dropping Nvidia as a partner and supplier. The NV2 never came to market, and when Nvidia failed to recoup its investment, the company almost folded. Nvidia dropped its spherical approach in one of the PC industry’s most daring turnarounds, repositioning the company to a polygon design. In 1997, it introduced the Riva 128—one of the most successful graphics chips of all time.

This article is part of the Electronics History series: The Graphics Chip Chronicles.