Understanding the 2023 Chip Market Collapse

This article is part of the 2023 Electronic Design Technology Forecast issue.

What you'll learn:

- What forces are causing the downturn?

- What could create a change in the cyclic nature of the market?

Last year, Objective Analysis predicted 6% growth based on the assumption that the surge in late 2021 would end sometime this year. Well, that surge has indeed ended, and the industry is now poised, through a significant downturn, to achieve that number. With the market falling back to its normal growth patterns after being overheated, it poses the likelihood of a drop of nearly 20% for 2023. Let’s see why.

What is “Normal”?

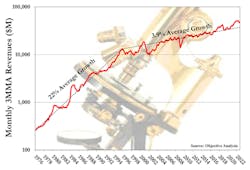

In 1996, the semiconductor market underwent a dramatic change. While annual revenues had been growing, on average, at a 22% rate, it suddenly dropped to 3.9%, a level that the market has followed for the past 25 years (Fig. 1).

This chart plots monthly revenues, as reported in the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics (WSTS) from January 1976 through last October. These are three-month moving average figures (3MMA), which WSTS uses to calm the dramatic spikes that naturally occur at quarter end.

The chart is plotted in a semi-logarithmic format, a format in which steady growth appears as a straight line. The two straight lines superimposed on the data are the 22% average growth trend followed from 1976-1995, and the 3.9% growth that the market has followed almost slavishly since then.

There are some notable departures from the trend over the past couple of decades:

- The 2001 Internet Bubble Burst, which left revenues below trend for over two years.

- Another dramatic drop below trend during the Global Financial Collapse of 2008-9.

- A significant rise above trend in 2018, when the U.S./China Trade War drove panic inventory builds in China.

- Another similar rise in 2020-22 driven by COVID, as the internet was built out to support telecommuting, remote education, home entertainment, etc., while new PCs were purchased for the same reason.

As vaccinations became pervasive and much of the workforce returned to their workplaces, the internet buildout has slowed, as have PC sales. Add to this China’s COVID lockdowns, which have stifled consumer spending in a country that now accounts for a significant share of global consumer demand. These two developments have caused revenues to decline, with the likely outcome that they will return to their pre-COVID trend. That means lower growth in 2022, and a decline in 2023.

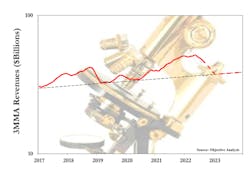

Here’s how that looks graphically. Figure 2 zooms in on the past six years in Figure 1, and extends revenues through 2023.

The red dashed line is a very simple forecast, showing revenues falling to the trend by the end of this year, then remaining right on the trend line through 2023. Given that revenues followed this trend very closely from 2004-2017, it’s a reasonable outlook for the market.

Different Approach, Same Result

It’s not the normal way that Objective Analysis forecasts the market. Our standard process is based on memory byte consumption growth and standard pricing patterns. This process is spelled out in great detail in Objective Analysis’ 2022 forecast. In brief, the model focuses on memory, the most volatile part of the market, and then predicts total semiconductor revenues based on a solid memory forecast. For the past 15 years, such an approach has proven to be the most accurate in the industry.

This forecast methodology provides us with a similar answer: Since memory prices are falling, it’s likely that they will reach cost by year’s end. If memory continues to be sold at cost for all of 2023, then total 2023 semiconductor revenues should be about 20% lower than 2022’s annual semiconductor revenues.

Will memory really be a profit-less business through the entire year? History tells us that overcapacities nearly always take more than a year to resolve, and this oversupply may be worse than most. Demand is returning to normal growth rates after having been overheated for the pandemic. However, leading DRAM and NAND producers have recently added capacity to sustain the higher level of byte growth than experienced by the pre-pandemic market. Now that demand is returning to normal levels, there’s excess capacity.

The market will not exit the current oversupply until demand catches up to today’s production capacity level. That’s unlikely in 2023. As long as there’s an overcapacity, chips will sell at cost. Producers are cutting capital spending as rapidly as possible, but they’re only promising real reductions in 2023. Since such cuts usually take two years to turn into undercapacities, that sets the stage for a real shortage in 2025, with a return to profitability most likely beginning in mid-2024.

Of course, this ignores the type of situation that has caused the last two cycles: 2018 was driven by a trade war, and 2020 was driven by COVID. It’s beyond any powers of mine to predict such phenomena, so this leaves the possibility that some event of global significance, like a COVID-driven meltdown of China’s economy, or a massive escalation of Russia’s Ukraine invasion, or some mad nuclear move by North Korea, could completely change the market’s outlook

Will incentives like the CHIPS and Science Act in the U.S. have any impact? It’s unlikely. Incentives tend to influence where manufacturers build fabs that they planned to build anyway. They provide “just enough” motivation to put a fab in a particular region. The location of these fabs has no impact on revenues or the supply/demand balance.

The big exception is government financing of new entrants that weren’t already in the semiconductor business, as is happening in China. So far, this effort isn’t having the anticipated impact.

With the U.S. applying restrictions on China’s equipment purchases, the country’s entry into the chip market should be further delayed. Such restrictions don’t only negatively impact the target country, though. Countries outside of mainland China, including the U.S., Europe, and even Taiwan and Korea, suffer repercussions of these moves. Although the effects of this are very real, we don’t make any assumption that our forecast’s accuracy is good enough to try and incorporate such elements.

Kioxia and Micron announced wafer production cutbacks. We will see if these are sufficient to bring the market back into balance. Since those wafers that just entered the manufacturing line will remain in process for about one quarter, it will take some time for the cutbacks to begin to have an effect.

Something else to consider is that a wafer start reduction never turns into a proportional decrease in byte production. It’s not even close! Those who would like a thorough explanation of this are referred to an Objective Analysis brief: “What a 5% DRAM Wafer Cut Really Means.” Meanwhile, Samsung continues to plan to increase its wafer starts. Given that today’s DRAM byte growth doesn’t require any new wafers, it’s an ominous sign.

Will the Market Recover?

What the arguments above tell us is that we’re unlikely to see a semiconductor recovery anytime soon, and that 2023 is nearly guaranteed to undergo a significant revenue decline. To express these in dollar terms, we see 2022 ending with revenues of $570 billion, falling to $460 billion in 2023.

On the plus side, it’s a return to normal for an industry that continues to grow better than almost any industry on the planet. But on the negative side, this means that the astounding growth we saw during COVID seems to have drawn to its natural end.

But semiconductors are notorious for “boom/bust” cycles. The market will most likely return to health in 2024 to enjoy another boom before a subsequent collapse, probably in 2026.

Read more articles in the 2023 Electronic Design Technology Forecast issue.