7 Technologies that Will Change Everything

Many years ago, when I moved to Silicon Valley, technology was undergoing massive change and was poised to make massive inroads, changing our lives as we know it. Although nobody expected this startling progress to last forever, the excitement continues, with newer technologies still poised to make massive inroads, changing our lives as we know it.

Let’s look at some of the current technologies that are likely to create significant change over the near term:

Generative AI

Probably the darling of the industry, this new approach to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) doesn’t limit itself to recognition and learning. It goes the additional step of reviewing phenomenal volumes of data to create reports, designs, and manipulated images faster than any human being.

What will be its impact on chip demand? Well, it takes such a huge amount of data that few organizations can afford the hardware or even the electricity to run it, so it’s fallen into the domain of the internet data center, where numerous users can access it over a 24-hour day.

Generative AI is likely to be embodied by a pretty small number of colossal computing machines that, put together, will account for a very small share of chip consumption. Even so, its use should change our lives.

Electric Mobility

It seems like everyone here in Silicon Valley (and probably in most other urban areas) is moving around electrically on eBikes, electric scooters, electric and hybrid cars, electric skateboards, unicycles, and Segways.

All of them require power conditioning and batteries. Some require fancy balancing controllers, and the autos include driver assistance. This is fertile ground for designers and electronics suppliers as a growing share of the world’s transportation budget will be devoted to electronics over time while this exciting field blooms and matures.

MRAM, ReRAM, Other?

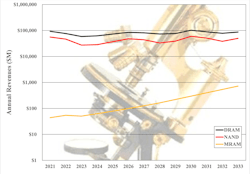

Whether it’s because of tightening process geometries or concerns about power, existing memory technologies are already seeing emerging memories nibble away at their markets. MRAM and ReRAM have seen rapid adoption for embedded program and data memories in wearables and IoT endpoints. Their use will grow over time to create a $44 billion market by 2032, according to a report recently published by Objective Analysis and Coughlin Associates (Fig. 1).

As their application broadens, unit volumes will rise, allowing the economies of scale to drive down their prices. Today, these and other emerging memories compete against NOR flash and SRAM. But as their price continues to decline, they will encroach upon DRAM and NAND flash, eventually replacing them altogether. Expect big changes in both the kind of memories used and in the applications that they enable, as their technical advantages led to the development of new usage models.

CXL

DDR DRAM has nearly run its course, migrating over the past two decades from DDR1 through DDR5. A new approach will arrive to support the voracious data needs of high-end processors, and CXL is poised to take on that role (Fig. 2).

Although CXL today appears to require no more than a sophisticated controller and standard DRAM, expect the sophistication of the controller to increase even as its price shrinks. This will have a major impact on systems design, first in hyperscale data centers, but eventually migrating down to all levels of computing, including PCs and cell phones.

Chiplets & UCIe

The limitations of modern photolithography equipment have stopped die sizes from growing, which was one of the three components Gordon Moore identified in 1975 that drove Moore’s Law forward. Chip designers are just now moving to chiplets to keep Moore’s Law on track.

So far, the communication between these chiplets has been proprietary, but UCIe (the Universal Chiplet Interface) is destined to change that. This will drive important costs out of the chiplet approach to broaden its use. Today, chiplets are found in high-end processors, but eventually, UCIe will be used to cost-reduce chiplets so that they will find homes even in modest SoCs.

In-Memory Compute

For decades, computer designers have hungrily looked at the kilobit-wide data paths within memory chips and dreamed of ways to harness that bandwidth by adding processors to the memory chips themselves. This approach is just now beginning to gain a reputable following through experiments like Samsung’s Aquabolt XL. Many others are working on similar efforts, but expect it to take some time for this technique to catch on.

Two factors are poised to stall it: One is that it requires software changes, and those conversions are always implemented extremely slowly, even if they aren’t that hard to develop. Nobody wants to take the chance of introducing new bugs into time-proven code. The other factor is that it drives up the cost of a memory chip, and system developers greatly dislike costly memory. Still, exciting change is in the air!

Computational Storage

Computational storage is very similar to in-memory compute, since it adds smarts within the storage device (SSD) or storage array. This approach isn’t driven by the huge bandwidth advantage that drives in-memory compute, but it’s instead aimed at reducing I/O traffic between the server and storage device.

While today’s advocates see computational storage as a programmable device that can offload varying tasks from a server, my guess is that we will see SSD-based smarts used mainly in fixed-function devices like those now provided by IBM, which compress data and perform primitives to help detect ransomware before it’s used in an attack.

Exciting Times

I’m sure that readers will note several other new technologies I’ve overlooked, and that’s a good thing, since it means the excitement in this field will continue for a long time to come. Feel free to use the Comments section to add your favorite new technology.