Now Eyeing Global Adoption, micro:bit Wants to Turn All Kids into Inventors

By Brian Fuller, Editor-in-Chief, ARM

Cultivating young innovators in the technology industry is of top importance for Zach Shelby, CEO of micro:bit Educational Foundation.

“Every child will be an inventor,” he says. “Technology is becoming an integral part of society that everybody uses. It’s not just for engineers and coders.”

“When you think of technology, it’s a skill set; it’s not a particular technology. JavaScript might not be around in 20 years, so it’s that skill of having an idea, planning it, designing it and using technology to solve the problem.”

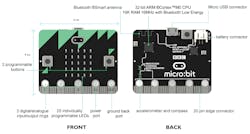

Shelby knows this first hand. He began his career as a teenage technology entrepreneur, repairing PCs and teaching computer skills for the public. A couple of decades later, he’s CEO of micro:bit Educational Foundation, which aims to turn the Maker movement on its head and deliver on that vision of making everyone an inventor using micro:bit (see the figure) as the place to start.

The micro:bit module has an array of LEDs on one side and a Nordic Semiconductor Cortex-M0 microcontroller. It also has an accelerometer, magnetometer, Bluetooth, and USB support.

Entrepreneurial Jump Start

“I’m interested in getting kids interested in being entrepreneurs,” says Shelby.

Kids like Ross Lowe, a 16-year-old U.K. student who got the maker bug and started using micro:bit, which led to his company, Bross Computing, and a product, Maker’s Kit for micro:bit.

The kit features a rotary potentiometer, a bi-color LED, a piezo sounder, and ports for connection to a breadboard with bundled jumper wires. The purpose of the kit is to allow users of the micro:bit to code physical components without worrying about losing individual components or struggling with wiring electronics. The kit screws directly onto the micro:bit, allowing inventors to take their projects with them.

Shelby was so taken with Lowe’s story that he had him join him onstage during the BET conference in January.

Ross Lowe is just one element of a movement that started a generation ago with the predecessor to micro:bit and ARM, the BBC Micro. The BBC Micro was a series of microcomputers and peripherals that Acorn Computer built for the BBC Computer Literacy program in the 1980s. ARM, founded in 1990, grew out of Acorn. Work on the micro:bit, an ARM Cortex-M0-based development board, began several years ago with the initial intent to distribute a board to every year 7 student in the U.K. (11 and 12 years old). That’s roughly 1 million devices.

The idea is to place easy coding and development capabilities in the hands of young innovators, and encourage a passion for STEM and invention.

To scale adoption, a more formal organizational effort was required, and that led to the development of the micro:bit Educational Foundation, which Shelby, vice president of IoT marketing for ARM, heads as CEO. The Foundation’s momentum is picking up steam, with roughly 1 million U.K. students receiving the initial wave of micro:bit devices last year.

“The cool thing is we have made good traction in internationalizing this,” says Shelby. In October, when the project was announced to the world, micro:bit had staked out territory in the U.K. and Iceland. Now, it has users in 70 countries with rollouts happening in Croatia, Singapore, and Norway, and a national pilot project in Finland.

Despite the ambitious number, the road to putting micro:bit devices in the hands of 100 million young inventors over 10 years is looking fairly straight and clear. By the end of 2019, some 5 million micro:bit kits will have been distributed.

But the biggest scaling challenge lies ahead: micro:bit launched in North America June 20, and expands into Asian countries this fall, including China, Japan, Korea, India, and Sri Lanka.

It raises an interesting question for Shelby, a serial entrepreneur who has started numerous companies as an adult: How to plan for and manage such scaling. Is micro:bit biting off more than it can chew?

“Not yet,” he says. “Right now people want the kit but don’t have access. Sure, we have availability in 34 countries, but we don’t in others that have shown interest, and that is a big opportunity.”

When asked if scaling the micro:bit Educational Foundation is different than scaling a startup, Shelby notes similar characteristics.

“Running any organization is running a business: You have to take in money and manage it, and you have to spend money. You need computers, IT people, lawyers, services; but we’re independent, and we don’t have corporate resources like human resources and legal. That’s like any other startup—lean, agile, virtual.”

And just like any other startup, a foundation needs a vision, he says.

“You need to make sure the vision motivates users, partners, staff, and volunteers in the field. It’s the same whether you’re making money or you’re a nonprofit.”

Spreading micro:bit’s Appeal

In addition to the vision, there’s the technology.

“Similar development platforms like Arduino and Raspberry Pi are nerdy. They’re made by engineers for engineers, so the audience is the maker audience,” says Shelby. “And those guys are wonderful, but that’s not how you have an impact with the public.”

“micro:bit is simple to use and doesn’t require technical knowledge. It’s non-nerdy,” he says.

Users can code via a web browser or download an Android or iOS app to send code wirelessly to the board via Bluetooth.

“What you can do with it is pretty unlimited,” says Shelby.

That’s job number one— making the technology easy and accessible. The second job for Shelby and team is convincing teachers and parents to support micro:bit, which is a bit more challenging.

“In schools, we’re limited to what teachers are willing to teach. They’re not always comfortable with teaching technology.”

Having a mobile interface is helpful, as micro:bit’s target audience has grown up using mobile phones. But Shelby is sensitive that not all schools have adopted new technologies.

“There’s a risk with this technology appearing in wealthy public-school districts and not those in less-advantaged areas,” he says.“ We’re focused on how we can have an impact on national rollouts—the whole country, every school.” There’s another potential challenge that could be an unintended consequence of success.

“There’s a risk that it becomes too commercial,” Shelby says. “As a foundation, we don’t want it to be that, and that’s why we started as a nonprofit. There is a value chain with resellers and accessories, but that shouldn’t be the main goal.”