A new software tool simulates the spots on a circuit board where processors and components are likely to fall off or become dislodged from vibrations that automobiles, airplanes, or satellite systems might go through, so that engineers can find issues earlier and improve the reliability of their products.

This week, Mentor Graphics added a software tool to its Xpedition software environment to rope electrical engineers and layout designers much earlier in the process of vibration and acceleration analysis that has normally been handled by mechanical specialists or testing labs.

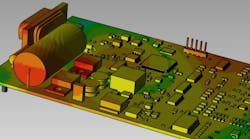

In a demonstration, the software applies stress to the virtual board and highlights for engineers the areas based on failure probability. Components that are a high-risk are red, while lower risk areas are yellow. Zooming closer into the pins holding down the parts, where failures often occur, shows a similar pattern of stress.

Normally, a company will rent out space in a testing lab with a shake-and-bake machine that tests devices until they fail. These physical tests are known as HALT, or highly accelerated lifecycle testing. But these types of tests costs thousands of dollars, the process is lengthy, and results may vary.

This type of testing is typically done before manufacturing, so getting it right is essential. And an extra layer of security is also helpful since failures can be costly – fixing the electronics in a single car is one thing, but having to do a recall to fix them all is different.

That has been supplemented with mechanical analysis software that mechanical engineers start using before sending a product or part off for physical testing, but that provides only basic understanding of where vibrations or acceleration can ruin boards.

“On a mechanical tool, the parts would be boxes and cylinders with no intelligence,” said David Weins, a product manager at Mentor Graphics, talking about how processors or capacitors. But the new tool adds an extra layer of detail to what mechanical specialists know about possible failures.

“We wanted to bring the validation and verification directly next to where parts are introduced so that the find-and-fix process can start sooner,” he said, adding that the new software could be used by board layout designers before it is even sent off to mechanical specialists.

Last year, Mentor Graphics agreed to be acquired by Siemens, which said it planned to fold the software makers into its part of the product life cycle management software unit. The group sells software to help companies manage the life-cycle of a product, from design and production to service and disposal.

The new software dovetails with the idea that electrical and mechanical engineers are collaborating more closely with each other on electrifying and smartening up mechanical designs. The Xpedition software is designed for big teams working on big products, and with the new tools the electrical engineers can hand off the board design having identified all the obvious failure points.

The Xpedition software contains a library of over 4,000 unique 3D component models, which are used to create highly defined parts for simulation. It can model screws, washers, and the jig that would normally hold the board or product during physical tests. Designers can import two dimensional parts into the 3D environment.

The company says that the new tools predicted 93% of the failed components in hours compared to three to five days for each physical HALT. Weins said that the software significantly reduces testing costs and outputs pass/fail for parts.

The program can detect components on the threshold of failure that would be missed during physical testing. It can also analyze pin-level Von-Mises stress and deformation to determine failure probability and safety factors. This results in increased test coverage and shortened design cycles to ensure product reliability and faster time to market.

“What we’re driving for is first-time-right designs,” he added. “We’re not trying to replace HALT tests or mechanical analysis.”