LEDs Line Up To Replace Residential Incandescent Bulbs

With the ubiquitous incandescent light bulb passing 130 years in age, we should have an economical and efficient replacement by now. Compact fluorescent lamps (CFLs) boast higher efficiency but include toxic mercury. Other candidates such as exotic RF plasma bulbs have been investigated for non-commercial use, but they have issues as well.

Previous LED replacement fixture (bulb) designs have been relatively expensive and suffer from poor life spans, even though they have excellent efficiency. But as other market forces beyond efficiency drive the selection of next-generation residential light sources, LEDs are standing their ground.

This file type includes high resolution graphics and schematics.

A Bright History

Artificial light has been with mankind since the dawn of the fire age. It has let us continue activities that normally would require daylight and extended the time when people could be social or productive. The arrival of oil lamps and candles civilized artificial light into a technology for extending the day past sunset. With the industrial age came gas lighting, which lined the streets of many cities. Yet it wasn’t until the late 19th century that electric lighting, first in the form of arc lamps and later incandescent filament lamps, was introduced.

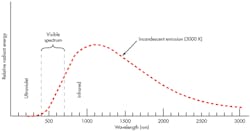

For more than 100 years, the incandescent bulb was ubiquitous in homes across most of the globe. But only a small percentage of its light is visible, and this trait has been well exploited. Over 90% of the emission spectrum of an incandescent bulb falls in the infrared (non-visible) range (see the figure).

Incandescent light bulbs are highly inefficient for visible lighting tasks, and replacements have entered the market. Competing technologies such as florescent lighting and low-pressure metal lamps are now widely available. The CFL often has been used as a symbol for eco-friendly technology due to its high efficiency, despite the small amount of toxic mercury metal it includes.

Today there are many options for lighting technology, mostly driven by the need for higher efficiency. Some lighting technologies such as high-pressure sodium (HPS) lamps achieve extremely high efficacies on the order of 150 lumens per watt (lm/W), primarily because the strong atomic sodium D-line emission mostly is in the visible spectrum. They also exhibit long lifespans on the order of 20,000 hours until failure. These lamps can be found in street and outdoor area lighting. But due to the strong yellow emission, they are not optimal for general lighting.

Solid-State Lighting

In the last 10 years, great improvements have been made in the efficacy of LED emitters. White LEDs with efficacies exceeding 100 lm/W are common. However, there are cost constraints still associated with LED lamps. To help bridge the gap, the U.S. Department of Energy hosted the L-Prize contest to drive competition and reduce the price of producing LED bulbs. Philips won the 60-W L-Prize, and the bulb is available for purchase today. All of the bulbs entered in the contest are designed to retrofit a standard fixture, and standard TRIAC dimmers can dim many of them, including the Philips design.

Related Articles

• R.I.P. Incandescent Light Bulbs: 1879-2013

• You can have my incandescent light bulbs when you pry them from my cold dead hands.

• Great Thermal Design Enhances LED Reliability

Nevertheless, the need to be compatible with dimmers and operate off of higher voltages found worldwide complicates the electronics and raises the cost of the bulb. Additionally, these bulbs only replace the conventional bulb in a standard fixture. For example, the BR30 light is found in many homes with recessed lighting across the U.S. It screws into the standard Edison E26 (26 mm) socket, which only supplies high-voltage (110 V ac) alternating current.

Such replacement LED lights must deal with an environment designed specifically for the incandescent bulb. Most of an incandescent filament-based light source’s emission is in the infrared range, which is heat. The heat is “radiated” away from the bulb, which has been exploited as heating elements for restaurant passes and the early Easy Bake Ovens from Kenner (later Hasbro).

LED emitters, however, do not radiate waste heat. They need to conduct it away instead, which introduces yet another engineering challenge in retrofitting a fixture designed more than 100 years ago. This leads to strange looking designs with fins and sometimes even active elements, such as the Nuventix SynJet cooling technology.

The Future Of Residential Lighting

There is a market for millions of replacement bulbs that are far more efficient than the old incandescent versions. Still, other forces beyond energy savings ultimately will drive more sophistication into home lighting. Beyond efficiency, LEDs offer additional features that have yet to be fully realized by designers, such as the ability to change color.

Tricolor (red, green, blue) fixtures allow color mixing, which can change the look of a space and affect mood. A recent area of study called color psychology is connecting colors with feelings. The color blue, for instance, is thought to instill feelings of relaxation and comfort. Using this knowledge, Boeing’s new jets have tray lighting with blue and white LED emitters to help passengers relax.

The ability to change color brings another dimension to the traditional dimming paradigm, requiring controls either in the infrastructure or the fixtures themselves. One solution is to add wireless technologies such as ZigBee, 6LoPAN, or 802.11 (Wi-Fi) inside the fixture, along with standardized protocols for communication. Controls then can be as simple as a mobile application on a cell phone to change the color or level of lighting in a room.This file type includes high resolution graphics and schematics.

The major problem today is the lack of standards for both the communication physical layer and the protocol. Unlike the simple and ubiquitous E26 socket, a wirelessly connected mesh networked light fixture needs standards for adoption. The industry may find applications in commercial settings first, but ultimately a minimum number of standards will be required for this kind of control to reach the home.

When it does, a new power system will be needed. Like the E-Merge Alliance commercial standards proposals, there needs to be a residential dc power grid. High-voltage transmission won over Edison’s dc transmission by reducing the resistive losses in cables over long distances. (Ohms law: higher transmission voltage lowers the effect of the fixed R term in P = I2R by reducing the “I” or current term.) This is fine for large-scale transmission, but most of our modern devices run on dc low-voltage power.

Every electronic device that has an ac power plug also has a complex power supply to convert that high voltage to the correct internal dc voltages required to operate the electronics. Several proposals for a standardized dc connector, or at least a residential dc bus, have been introduced. However, no standard yet has been adopted. Additionally, a dc plug standard could also bring Ethernet or other wired communication standards into the plug, allowing for a physical layer that is already widely deployed.

Conclusion

Residential lighting designers and suppliers will move as an industry to the more sophisticated lighting technologies only when the standards are ratified. These will include both power (most likely dc) and communications to take advantage of the capabilities that LED lighting has yet to realize, which goes beyond the efficiency benefits. In the home of the near future, replacing a bulb will be passé, and the ability for the structure to affect the occupant’s mood by altering the color will be as common as dimming that old incandescent light fixture.

Reference

For more information about LED lighting, visit www.ti.com/led-ca.

Richard Zarris a technologist at Texas Instruments focused on high-speed signal and data path technology. He has more than 30 years of practical engineering experience and has published numerous papers and articles worldwide. He is a member of the IEEE and holds a BSEE from the University of South Florida as well as several patents in LED lighting and cryptography.

This file type includes high resolution graphics and schematics.

About the Author

Richard F. Zarr

Richard Zarr is a technologist at Texas Instruments focused on high-speed signal and data path technology. He has more than 30 years of practical engineering experience and has published numerous papers and articles worldwide. He is a member of the IEEE and holds a BSEE from the University of South Florida as well as several patents in LED lighting and cryptography.