Standards, standards, everywhere. That could be the refrain for those who are designing the next generation of energy-efficient products. Whether it's power supplies, white goods, motorized equipment, or TV sets, there is a whole host of mandates that, one way or another, specify minimum power efficiencies.

Problem: There is no such thing as a global efficiency standard. Each region of the world tends to tailor its efficiency mandates in ways reflecting its ecopolitical environment and the lifestyle of its population. So designers who build systems for worldwide markets must navigate a variety of region-specific dictates.

“Europe's focus appears a bit more environmental, toward the restriction of hazardous substances (RoHS) and toward Green,” says Moe Kabiri, applications engineer at Cosel (San Jose, Calif.), a power-supply manufacturer. “The emphasis is on components, more than efficiency. Power-factor correction (PFC) is important, but noise emission is more of a concern. In contrast, there are no laws in the U.S. that demand enforcement of harmonic distortion. And no U.S. agency is actually responsible for PFC (a related but separate issue).”

Indeed, electrical specs are in fair agreement across the various global standards bodies. But they're not close enough overall in most cases to permit inventorying, say, a single-platform, universal power supply design.

At the same time, there's notable progress in both the electrical and environmental arenas. The standby spec of 1 W for portable supplies, considered a formidable challenge little more than a decade ago, is well on its way to being supplanted by a 0.3-W metric or less, even for some power supply designs delivering several hundred watts. Similar trends are in place for industrial motors and lighting systems. And there is an increasing emphasis on tightening the “equipment envelope;” i.e., the infrastructure of office buildings and installations that house power equipment. This movement is struggling for official status across the U.S. If what has happened with other efficiency standards is any indication, designers of equipment for overseas markets will soon have to contend with similar measures.

So near but yet so far

The engine for standards development consists of a complicated mix of voluntary and mandatory documents and standards groups that feed off each other. In the U.S., many efficiency standards are voluntary. In other parts of the world (particularly Europe), they tend to be mandatory. Regardless of their origins, most standards are the product of lengthy discussions and complicated negotiations. It is not unusual for a typical standards document to comprise perhaps 30 different product categories.

Though different regions generally enact their own standards, there is often a lot of commonality with standards adopted elsewhere. That's because standards bodies tend to mimic the best practices spelled out in specifications adopted by other parts of the world. So it is not a bad strategy for product developers to “follow the leader” when it comes to efficiency standards. Good ideas tend to migrate around the world even if requirements aren't completely harmonized.

But there are on the order of 20 different standards groups worldwide. It is tough to get the national organizations overseeing these groups to agree on mandatory, universal adoption of their output. Nevertheless, there are signs efficiency standards are moving forward worldwide. “All industrialized nations recognize that energy consumption is going to continue to escalate, and the creation of new generating stations is not the sole answer. Energy efficiency has to be an equal partner to reconcile sustainability,” says Terry Drew, Director of Energy Efficiency for CSA International (Ontario, Canada), which tests products for compliance to national and international standards, and issues certification marks for qualified products. “Everyone is coming from the same viewpoint. It's more a matter of implementing or developing regulations at various stages or rates.”

Continue to next page

Most efficiency standards tend to be works in progress, thanks to continually improving power conversion technology and to an increasing body of knowledge about efficiency techniques. This sort of on-going improvement leads to much give-and-take over new or revised standards. It also implies there is no such thing as a universal or “best” standard.

Still, some standards have more worldwide clout than others. Examples include the minimum energy-efficiency specs initially imposed by the so-called European Code of Conduct (which are voluntary) and its connecting organizations (which deliver both voluntary and mandatory documents, the most recognized being their European Norms, ENs). These remain by most accounts the “gold standards” for efficiency in TVs and in power supplies within consumer goods. But the California Energy Commission is also highly respected for its approach to innovation and establishing mandatory standards in the Golden State. By the same token, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Energy Star program goes significantly beyond the minimum requirements set by the U.S. Dept. of Energy. Though it is strictly voluntary, Energy Star is often a step ahead of the EU and is widely viewed as the initiator for many major standards worldwide.

Standing by

Designers have two major goals when they set out to improve energy performance: minimizing what a device consumes in its standby mode, and maximizing supply efficiency across a wide range of loads.

The well-known 1-W standard for quiescent power dissipation originally applied to portable devices. Today a 1-W standby spec even for advanced systems seems way too high for most system designers. Representative estimates place the “lost energy” associated with standby power at somewhere around 10% of total draw from the home. The 1-W challenge was formidable in the era of wall-type power supplies of the 1990s. Now, in most places and for most small devices, designers aim to halve that requirement. At worst, now the standby power spec is perhaps 2 W for the most power-hungry of systems. Today the challenge is in half-watt standby. Making things more difficult is the increasing use of various microwatt devices having numerous watchdog functions. All those timers add up. So cutting a portable device's standby power from 1 to 0.5 W takes some doing.

Nevertheless, customers want the half-watt standard tomorrow. Actually, they'll get it about 2013. “The one-watt standby wasn't a real tough issue,” says Rich Fassler, Energy Efficiency Programs Manager for Power Integrations (San Jose, Calif.). “But the half-watt is.” Fassler also alludes to some of the complexities that multiple standards introduce for designers trying to hit this spec. “For example, as a Chinese designer working on a silver box in a computer, I've got to become aware of the EU Eco-Design Directive of Energy-Using Products (EuPs) as well as how it compares to Energy Star's computer spec. And sometime at the end of this year the Eco-design Directive for Lot 3, which covers computers, will be approved by Parliament. And 12 months after that, it will be mandatory to meet those specifications.”

Then there's the question of overall power supply efficiency. Most designers consider a power supply with 80% efficiency obsolete. So the Energy Star 80 Plus initiative has given way to a four-year program (often referred to as the “90 Plus” standard) trying to exceed 90% efficiency by 2011. At this point, though, designers have done almost all they can to tweak power supply topology. Indeed, the main factors have already been addressed; e.g., cutting the switching and conduction losses of the power MOSFET stages and the equivalent series resistance of the supply's inductors. So the next 10% improvement in efficiency is likely to take more effort than the last.

Indications are that Europe will adopt the same measures. “There are no significant differences between the Energy Star program and what the European committee recognizes,” says Loic Moreau, Business Segment Manager, New Business for LEM (Geneva, Switzerland), a maker of current and voltage sensors. “We have an Energy Label mainly for white goods. I don't have a conviction that the European Committee is starting on any new work; they use what's in effect.

Environmental issues, long of interest to the Europeans, have come to be just as prominent in standards as promoting a set of universal electrical specifications. “The only region of the world where customers request a list of the materials we use to handle the carbon footprint is from European customers. And where I do see changes is through the Eco-Design of Energy-Using Products Directive now in force,” says Moreau.

Continue to next page

The principle (for products having production volumes exceeding 200,000 pieces annually) is as follows: The manufacturer must take the life cycle of the product into consideration during conception, as well as how to make it environmental friendly, use less energy, and use less material. The manufacturer must also determine the appropriate Energy Label as well as how to reduce the product's impact on the environment through recycling and such. Even so, the most important impact on energy use during the life cycle of a product may have nothing to do with its manufacture or end-of-life. “For a Coca Cola bottle, 45% of the total energy over the life of the product goes into keeping the bottle cool in the refrigerator. So the ecosystem of the product may have a bigger impact than the production process or recycling method,” says Moreau.

Green issues

Green building specs have become the over-arching metrics for sizing up the ecosystem. “If the structure into which you're putting your electronics is not just as efficient as the enclosure, you're negating your gains,” says Moreau. In the U.S., energy service companies (ESCOs) are entities that make a business out of developing, installing, and arranging the financing of projects designed to improve the energy efficiency of facilities. Thanks to the widespread adoption of the LEED (Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design) standard for measuring building sustainability, they have had some success.”

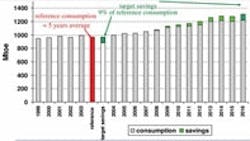

Going down yet another avenue, the EU's Energy End-use Efficiency and Energy Services Directive asks member states to reduce overall energy use (supply and distribution of electricity, heating, and natural gas and other fuels) by 1% per year out to 2017. Total savings would be 9%.

There has been a bit of controversy surrounding the Directive. The “controversy” was over the issue of targets for energy savings. Member countries originally didn't want to be tied to a timetable and steadfastly stated their preferences for a non-binding target. The European Parliament wanted legally binding targets. There was a compromise in 2005, the end result being the “agreement” for the 1% improvement in energy savings. The document was approved in 2006 and, for the most part, came into effect in May 2008.

Most parties have gone along with it. But the Eurelectric union (Europe's electricity industry) initially felt the agreement would place a disproportionate burden on the electricity producers, versus say, gas suppliers. Conversely, the World Wildlife Fund was one organization that felt the Directive was too weak. So some countries developed higher targets; and a few others claimed they couldn't get aboard the program until later in the decade (2015 or so). But presently the Directive is supposed to be legally binding and “mandatory.” At the same time, there is some evidence that some member countries haven't complied and haven't been fined. This is a grey area and no one has much to say about countries planning to go with the Directive but that are unable to at present.

Mandatory building directives in the U.S. are another issue. Curiously enough, however, ANSI Standard 90.1 (cosponsored by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers — ASHRAE) originated in the mid 1970s long before “green” was a buzzword. The standard originally just covered commercial buildings (low-rise residential buildings excepted). It has been updated numerous times through the years. A newly proposed version called 189.1, Standard for the Design of High Performance Green Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings, has the additional backing of the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) and the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America. USGBC, in addition, supports the LEED initiative. ANSI/ASHRAE 189.1 is intended to serve as the underpinning of future green building codes, but it's basically still a voluntary specification that, as with the bulk of green standards in the U.S., is still better characterized as moving toward a quasi-mandatory standard.

Residential and county standards groups drive many of the advisory standards, which number in the range of 100. The better-known residential initiatives include the National Green Building Standard, sponsored by the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) and the International Code Council (ICC). Several of these specs incorporate Energy Star initiatives in the overall package.

Continue to next page

Still, while large areas of the world don't subscribe to any given standard, virtually all have some kind of energy savings standards in place. Regions of the world with systematic, unified approaches, such as Europe, continue to have an edge on harmonizing test procedures and energy specs especially with Canada and the U.S. Central America taking the same tack. “In Central America, the countries are trying to develop or establish themselves as a block of countries to subscribe to a blanket set of requirements,” says Terry Drew. “It's too difficult to make inroads individually. But it's happening.” These countries tend to align more directly with the Europeans than with their northern neighbors.

The rest of the world is more than willing to participate at some level. “Pick a country, say, Brazil, South Korea, China, India — they have standards we might not hear about,” says Rich Fassler. “But most emerging countries realize that as the population grows and more people can buy things that plug into a wall, the demand will be met by being more efficient. Even Cuba has an energy efficiency program now of sorts -- swapping out incandescent light bulbs.”

Getting involved

With the changing standards landscape, it pays to keep up on current thinking of regulators. “If I'm a design engineer, I want to make sure I sign up as a stakeholder for all the different agencies,” says Fassler. You'll receive all the meeting notices, presentations from the meeting, and so on, an easy way to stay up to speed to a certain point. There's no need to get on a plane to attend a meeting -- there are Web conferences. It's not as good as attending in person, but still it's very good.”

As efforts take hold to arrive at ideal “global standards,” most participants see worldwide standardization as being at least a decade away. On the other hand, manufacturers that must serve multiple worldwide markets readily recognize the connection between universal standards and a need for smaller inventories. Today, mobile applications serve as an example of what might be possible from unified policies on energy efficiency. Cell phones, for instance, basically utilize common protocols everywhere in the world. Likewise, the charger/supplies that power them work from a universal line-voltage spec (85-265 Vac). Transmission standards for TVs, on the other hand, are different. Those differences ultimately trickle down to specific differences in power supply design. The same holds true in the white goods area.

“I don't know if we're going to see a global standard in the near future, but rather a will to try and be uniform toward energy efficiency and also to understand what other countries are trying to achieve,” says Terry Drew. “On the other hand, if we recognize there are different rates of evolution in development, we're likely still a long way off.”

Ecodesign Directive for EuPs Lot Status (4/1/10)

Continue to next page

The long wait for new standards

There are more and more efficiency standards all over the world. As they proliferate, it can be difficult to make plans based on what's coming down the pike in different countries. This is particularly true for Europe. “The problem for the engineer with such documents as the Eco-design Directive in Europe is that in creating the document, first a consultant studies the market, gets test data, and makes recommendations. Then the process kind of goes silent,” says Rich Fassler. “After the study is done, it goes to a consultants' forum. Typically, that consists of one consultant from each member state (country), and some other representatives. The public is not generally invited.”

From the consultants' forum, it goes to the European regulatory committee. The committee can send it back if they see a business impact or unfair competition. Upon regulatory committee approval, it goes to the European Parliament to be voted into law. It then goes to the World Trade Organization which evaluates it for any unfair competitive implications around the world. If all goes well, the European Parliament votes on it. Afterward, the standard gets published in the European official journal. Within a month after publication, it becomes law. Typically, it's another 12 months before it goes into effect.

This lengthy protocol can make some standards moot by the time they are enacted. “Take the case of Lot 3 (Energy Star v. 3, computers), which came up three or four years ago,” says Fassler. “By the time the consultants met, Energy Star had already moved ahead to its next version, which was a totally different way of measuring efficiency. It had a standby mode, it had an active mode, and it had certain levels of efficiency at different loading points. So it had all changed. It was a tighter efficiency specification. At the forum, a revised draft came out dictating harmonization with the new Energy Star version.”

For more information:

Cosel Co. Ltd., San Jose, Calif., www.coselusa.com/

CSA International, Cleveland, Ohio, www.csa-international.org/

LEM, Milwaukee, Wis., www.lem.com/

Power Integrations, San Jose, Calif., www.powerint.com/en/green-room

EU motor efficiency standards, www.ecomotors.org

EU Manage Energy site, www.managenergy.net

Approved Ecodesign Standards

(street and office lighting)

Apr 1 20, 2012 (on)

Aug 20, 2011 (standby)

**Additional efficiency tier Jan 1, 2017.