Super-efficient heat exchanger could be a game changer

April 10, 2012

Comments

Comments

It turns out that fluid swirled into a vortex can transfer heat more efficiently than when it is passed through the tubes of a conventional shell-and-tube heat exchanger.

This insight comes from Georgios Vatistas, professor of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering at Concordia University in Montreal. Vatistas, an expert in vortex dynamics, has patented the idea with doctoral fellow Mohammed Fayed and has produced a prototype said to be four to six times more efficient than the traditional shell-and-tube heat exchangers found in chillers.

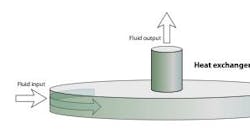

The basic idea behind Vatistas' heat exchanger is to put two cylindrical fluid chambers next to each other, routing hot fluid through one, cold fluid through the other. He pumps fluid into each of them in a way that causes swirling and creates a vortex flow. The swirling action, perhaps guided by vanes placed at strategic positions inside the chamber, promotes efficient heat transfer between the two chambers.

The resulting structure is a lot simpler than a conventional tube-and-fin heat exchanger. Vatistas says it can also be smaller than a shell-and-tube exchanger with the same capacity. The new design looks even better compared with a plate heat exchanger -- Vatistas says it was 40x more efficient with regard to the energy required by pumps to move the two fluid streams (hot and cold) through the two devices (traditional and new), operating under the same conditions. The comparisons were made using data from a comparably sized commercial plate exchanger.

Vatistas sized the new exchanger prototype using specially modified is made using the commercial computerized fluid dynamics software (Fluent 6.2) that his team modified for vortex analysis. He also says the performance of the new exchanger depends on the dimensions of its parts and on the properties of the working fluids. The only limitations he's run into concern cavitation of the liquids near the central axis, if the dimensions (in conjunction with the thermo-fluid properties) are not properly selected.

So far, Vatistas has been using water as the working fluid for both streams. But based on research thus far, he says, he sees nothing to prevent using gasses or a liquid/gas combo as a working fluid. "As a matter of fact, because the passages are relatively large, the present devise should also be very suitable for slurry flows," he says.

At the present, he also foresees just using pumps or compressors to push fluid through the system, rather than moving to more exotic means.

Valeo Management LP in Canada has plans to commercialize Vatistas' work: http://www.gestionvaleo.com/en/activ.html

A copy of Vatistas' patent text is here: http://www.rexresearch.com/vatistas/vatistas.htm

Concordia University in Montreal: http://www.concordia.ca/