Fluorescent and incandescent bulbs have been fixtures of the last century, but they are slowly dying out, replaced by highly efficient LED bulbs. But another form of lighting known as organic LEDs, which can be molded into panels and twisted into different shapes, has the potential to fundamentally redefine how we think about lighting.

The market for OLED lighting panels has been met with uncertainty in recent years. That uncertainty results from disagreements over what technology developed for OLEDs in smartphone displays can be transferred into OLED lighting. In general, though, predictions have been positive. The market is expected to reach almost $1.5 billion in 2021, up from around $30 million in 2015, according to a recent report from Yole Developpement.

OLEDs, like LEDs, are comprised of semiconductor material sandwiched between two electrodes. The difference stems from the fact that OLEDs are built using carbon-based material. The process for making OLED lights involves combining thin layers of red, blue, and green semiconductor films, which emit a soft white light when stimulated by an electric current. LEDs, on the other hand, usually combine blue semiconductor diodes with yellow phosphors to produce sharp points of light.

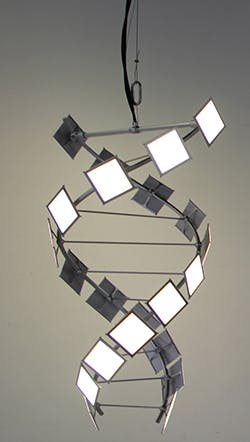

OLEDs can be spread over panes of glass, metal, and plastic to create a light source that radiates over a broader area than conventional LEDs. Adding to its unique qualities, the lights can be applied to flexible substrates, allowing them to be twisted and curved into different shapes. Like LEDs, they also have the potential to consume more than 75% less power than incandescent and fluorescent bulbs.

With properties similar to LEDs, OLED technology has gained widespread support. The U.S. Department of Energy is putting over $14 million into OLED research projects in 2016, and the European Union has set aside more than $15 million to construct a factory for flexible OLED panels. LG Display is building an OLED lighting plant in South Korea that would make around 15,000 glass substrates per month. Acuity Brands, an Atlanta-based lighting company, is already selling its Chalina and Aeden fixtures in stores.

“OLEDs are in a promising place right now,” Morgan Pattinson, an analyst with the independent consulting firm Solid State Lighting Services, said in an interview. While OLED lighting is not expected to replace LED, it can complement normal light bulbs in pendants, wall lighting, or any situation that calls for diffuse, natural light.

The technology still suffers from competition from standard LED bulbs, which can not only be produced at a fraction of the cost but also screwed into the same sockets as older lights. LEDs that generate the same amount of light as an 100-watt light bulb (1,000 lumens) costs about $10. To achieve the same with OLEDs, it costs about $1,000.

The relatively high price for OLED panels results from a factory process that requires significantly more material than LEDs. In addition, the manufacturing techniques are still imprecise, complicated by the task of spreading nanometer-thick film over large sheets of substrate. The result is a large number of defective units and low reliability when compared to LED bulbs. Minor flaws make the quality of light degrade faster than LEDs, an issue that companies have tried to combat with more expensive substrates.

As both the technology has matured, however, production costs have fallen. Almost five years ago, an OLED lighting panel with 75-watt output cost $2,560. The lights sold by Acuity Brands, which have an output similar to 25-watt bulbs, are priced between $200 and $350. Pattison credits the improvements to cheaper materials and new factory processes that waste less material. At the same time, OLED lighting has closed the gap in efficiency and lifespan with LED.

Contributing to these advances in assembly and materials are new developments in OLED displays for smartphones and televisions. Extremely thin and flexible, the displays are being used in products ranging from transparent Samsung televisions to Apple smartphones. Further advances in OLED displays could transfer into lighting and help lower production costs.

Pattinson cited advances in OLED displays made with backplanes of circuitry overlaid with red, green, and blue pixels. The process is similar to how OLED lighting panels are built, so that improvements in making backplanes could translate over to lighting. In addition, both industries have experimented with using inkjet printers to deposit OLEDs cheaply onto sheets of plastic or glass.

There are many companies in the market for OLED lighting, though bigger players like Panasonic and Philips have sold their businesses to more patient competitors. OLEDWorks, the New York-based company that bought the OLED division from Philips Lighting last year, has several products with 50,000-hour lifespans, comparable to LEDs. Mitsubishi’s lighting unit Lumiotec, as well as Kinoka Minolta and LG Display, have all developed flexible and colored panels for interior designers. Universal Display Corp., which licenses out OLED patents, recently agreed to develop new technologies with Osram Opto Semiconductors.

John Hamer, the founder of OLEDWorks, underlined the health of the industry at the Energy Department's annual meeting for the OLED industry last December. He compared the 48 participants at the meeting to the handful of researchers who attended the department’s first OLED workshop several years ago. At the same time, however, many of the companies represented at the meeting were struggling to sell lights. IHS Technology estimates that only 5,500 OLED lighting fixtures were sold in 2014.

Milan Rosina, senior technology analyst with Yole Developpment, suggests that widespread success would start in niche markets, including automotive, medical, and embedded lighting. “Lighting has evolved from a basic, functional feature to a distinctive feature with a high value potential,” she says. She pointed to the BMW as an early proponent of the technology, designing the 2016 M4 GTS sports car with OLED tail-lights.

Though the market for OLED lighting seems sluggish, Pattinson says that it has followed a similar pattern as LEDs. The lighting market takes a long time to digest new technology because it has become so focused on low costs. To its credit, OLED light has been likened to natural sunlight, whereas LEDs have sometimes been called cold and commercial. Other than that, “almost anything LEDs can do, OLEDs can do,” says Pattinson.