Laser-Driven Microscope Analyzes Magnetic Microstructures with Nanometer Resolution

What you’ll learn:

- The need for assessing magnetic fields on a microscopic scale.

- Solid-state physics for novel spintronic method.

- Why laser-based heating is beneficial.

- Physics principles of interest.

Analyzing magnetic nanostructures with a high resolution is a test-and-measurement challenge, but it’s important for both advanced physics insight as well as real-world products such as high-density hard-disk and tape drives. The miniaturization of spintronic devices requires individual magnetic entities to be densely packed, but magnetic stray fields due to the interactions between neighboring bits are a major limitation for the packing density when nanoscale ferromagnets are used.

[Incidentally, if you think that tape storge is an obsolete relic from the “dinosaur days” of computers, think again: Tape drives are still widely used for archival storage and off-site backup; it’s a huge and fast-growing market with about 10% annual growth, offering super-high-density tape cartridges and automated robotic cartridge-handling systems with pick-and-place racks.]

Addressing the magnetic microscope and resolution issues, a technique developed by researchers at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics in Halle enables researchers to analyze magnetic nanostructures with a resolution of around 70 nm, whereas normal light microscopes have a resolution of just 500 nm. Their result is important for the development of new, energy-efficient storage technologies based on spin electronics.

Magnetic stray fields due to the interactions between neighboring bits are a major limitation for the packing density when using nanoscale ferromagnets. An elegant solution, in use since the very first spintronic sensors and magnetic random-access memories, is to create a synthetic antiferromagnet formed from thin ferromagnetic layers. The layers are coupled via a thin metallic antiferromagnetic (AF) coupling layer.

Recently, there’s been increased interest in using innately AF materials for spintronic applications as these are free from stray fields. However, the absence of stray fields makes it very difficult to calculate the size, as well as image, AF domains. Typically, it’s understood that these materials exhibit domain structures at the submicrometer scale.

Solid-State Physics for Novel Spintronic Method

The new technique leverages several lesser known but important solid-state physics principles (solid-state here doesn’t mean silicon and similar devices as used in electronics); see the “Physics Principles of Interest” sidebar at the end of the article for a summary of these if you’re not familiar with or have forgotten them.

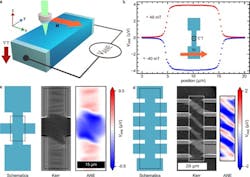

Their method overcomes the optical limit by using the anomalous Nernst effect (ANE) and a metallic nanoscale tip. The ANE generates an electrical voltage in a magnetic metal that’s perpendicular to the magnetization along with a temperature gradient (Fig. 1).

A laser beam focuses on the tip of a force microscope, causing a temperature gradient on the surface of the sample that’s spatially limited to the nanoscale. The metallic tip acts like an antenna and focuses the electromagnetic field on a tiny area below its apex. This enables ANE measurements with a much better resolution than allowed by conventional light microscopy.

They used a laser beam focused by a microscope objective to create a temperature gradient while scanning the sample laterally for imaging. By using laser heating to generate a local temperature gradient (ΔT) that can be raster-scanned across the sample, the spatially resolved measurements of ANE-generated voltage (VANE) enable the imaging of magnetic domains in both ferromagnets and antiferromagnets.

A 15-nm thick in-plane (IP)-magnetized Co20Fe60B20 film was patterned into a 10-µm-wide wire (called a racetrack nanowire) and a magnetic field is applied along the width of the wire. They observed a VANE signal on the order of a few millivolts as the laser beam was scanned across the wire.

Applying this method to a nanoscale spin texture of a magnetic vortex allowed them to understand the spatial spreading of the thermal heat gradients (Fig. 2). A magnetic vortex structure leads to a very rapid rotation of the IP magnetization as the vortex core has a width of only a few nanometers. The result is a nanoscale transition between opposing in-plane magnetization directions across the vortex.

An ANE line scan through the vortex made it possible for the team to compute the spatial distribution of the heat gradient, which is given by the derivative of the ANE line scan. The magnitude of the ANE voltage in a given magnetic wire is proportional to the total absorbed power that contributes to heating the wire, and inversely proportional to the wire width. The magnitude of the ANE signal is independent of all other geometric factors.

Why Laser-Based Heating is Beneficial

The laser-based heating used in ANE microscopy offers multiple advantages. First, the entire absorbed energy directly heats the wire, in contrast to resistive-heating methods where most of the heat energy is dissipated elsewhere. Second, since the voltage is inversely proportional to the wire width, studying narrow wires with ANE microscopy yields larger signals.

There are other benefits to this approach as well. Previous studies have only investigated magnetic polarization in the sample plane. However, according to the research team, the in-plane temperature gradient is also crucial and allows for probing the out-of-plane polarization using ANE measurements. Finally, since the ANE signal is directly proportional to the temperature gradient, researchers can consider the inverse problem and deduce information about the nanoscale temperature distribution.

This is a complex and somewhat esoteric project that could almost be confused with magic, but it does have some real-world R&D implications. The details are in their paper “Anomalous Nernst Effect-Based Near-Field Imaging of Magnetic Nanostructures” published in ACS Nano (American Chemical Society).

Physics Principles of Interest

- Anomalous Nernst effect (ANE): A phenomenon that generates an electric voltage in a magnetic material when a temperature gradient is applied. The voltage is perpendicular to both the heat flow and the magnetization.

- Antiferromagnetic spintronics device: These materials have internally ordered magnetic moments, but neighboring moments point in opposite directions, resulting in a zero net magnetization. This means they’re insensitive to external magnetic fields and don't generate stray fields, making them more robust and less susceptible to interference.

- Magnetic vortex: These form when electron spins swirl in a circle within a plane. At the center of the circle, the swirl becomes smaller and eventually the magnetization at the core tilts out of the plane, similar to a tornado.

- Racetrack nanowire: A tiny, magnetic wire used in a type of non-volatile memory called a racetrack—it’s intended to store data as a sequence of magnetic domains (bits) that can be moved along the wire like cars on a racetrack.

- Spintronics: Also known as spin electronics, this is a solid-state device technology that exploits the intrinsic spin properties of an electron and its associated magnetic moment, in addition to the more-familiar electron charge.

About the Author

Bill Schweber

Contributing Editor

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple topic-specific sites for EE Times, as well as both the Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN.

At Analog Devices Inc., Bill was in marketing communications (public relations). As a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these.

Prior to the MarCom role at Analog, Bill was associate editor of their respected technical journal and worked in their product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls.

Bill has an MSEE (Univ. of Mass) and BSEE (Columbia Univ.), is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.