High-Speed Interfaces Pushing Optical Connectivity

This file type includes high resolution graphics and schematics when applicable.

Being somewhat expensive, fiber-optic cables have traditionally been utilized where their advantages—like long distance—were worth the cost. Servers and long-haul connections have been typical use cases. But now, higher-speed connectivity requirements are pushing optical technology into more common use, even in the consumer applications, as well as pushing multiple fiber connections for building out the cloud to meet the demand for the Internet of Things (IoT).

Optical systems are simple, in theory. There is a light source at one end and a detector at the other. The light goes through optical cable and it is not affected by electromagnetic noise like a wired connection. While there is signal loss, it is significantly less than a wired connection, making fiber the preferred method for long distance connections.

Laser diodes or LEDs are the usual light source. Lasers include fabry-perot (FP), distributed feedback (DFB), and vertical cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSEL). Detectors include silicon photodiodes and germanium or InGaAs (indium gallium arsenide) photodetectors. Optical cabling is divided into single-mode and multimode types. The former has a smaller diameter and is normally used with a laser source supporting higher bandwidths and longer distances.

Fiber Optics and Consumers

Fiber-optic cables have tended to be used in specialty consumer applications such as digital video recording, where the connection quality and longer distances offset the cost. The typical connections include high-speed serial interfaces such as USB, Thunderbolt, and PCI Express. Fiber connections are also available for display technologies like DisplayPort and HDMI. In addition, fiber has been used in digital audio applications. S/PDIF (Sony/Philips Digital Interface Format) jacks are common on audio boards and components, including amplifiers and HDTVs.

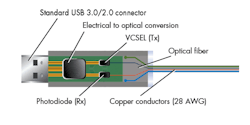

S/PDIF utilizes a passive fiber optic cable with the emitters and detectors embedded in the devices. Most other fiber-based systems employ an active cable with electronics at both ends. The typical example is Corning’s USB 3.0 cables, which include a pair of fiber-optic links and a pair of copper links with interface logic at both ends (Fig. 1). This approach eliminates the need for specialized fiber optic support at either end of the connection, since most applications assume a copper connection. This does increase the cost of the cable, but allows the technology to be used with existing systems. Typically the copper cables are passive.

Corning is a major supplier of fiber-optic technology; it sells optical USB 3.0 (Fig. 2) and Thunderbolt cables in 10, 15, 30, and 60 m lengths. Their ClearCurve ZBL (zero bend loss) technology essentially allows the cable to be tied in knots without breaking or signal degradation. Optical cables used to be less robust.

So what is changing? In a word, the Type-C connector.

USB 3.1 was the initial driving force behind the reversible Type-C connector. USB 3.1 Gen 2 runs at 10 Gbits/s. It is already being tapped for 40 Gbit/s for Thunderbolt 3.

The cables are also intelligent, often including redrivers on at least one end of the cable to handle the challenges of using copper connections that are normally under 3 m. This moves copper cable costs closer to optical. Optical cables are still going to cost more, but the mass market should help reduce these costs—especially as higher bandwidths are utilized.

Fiber Optics and the Enterprise

Networking has been the main use of fiber-optic cable in the past. This is typically Ethernet, but other networking and storage technologies like FibreChannel and InfiniBand support optical connections. Another new architecture is Intel’s Omni-Path fabric, which targets the cloud and high-performance computing (HPC). It is designed to scale to tens of thousands of nodes with connection speeds of 100 Gbits/s. Speeds continue to move ever higher and there is even 400 Gbit/s Ethernet on the drawing board. Optical connections will be key.

Most of these network adapters and switches embed the transceivers in the hardware or provide a small form-factor pluggable (SFP) interface. SFP was only the starting point. There is now SFP+ and QSFP+ handling 10 Gbit/s and 40 Gbit/s interfaces. Dell’s S4810 10/40 Gbit/s Ethernet switch (Fig. 3) has 48 10 Gbit/s SFP+ ports and four, 40 Gbit/s QSFP+ uplink ports.

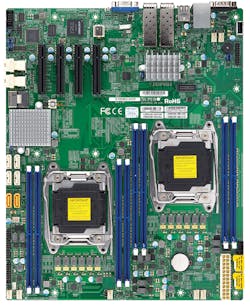

SFP modules include the optical transceivers and optical connections. Modules can support different passive cable connections including ST, FC, SC, and LC. This allows the cable lengths to be tailored to the installation. Super Microcomputers’ (SuperMicro) 10 Gbit/s SFP+ patch cable shows a pair of SFP+ modules with a short fiber optic cable (Fig. 4). Unlike Corning’s USB 3.0 cables, the SFP+ modules draw power from their host, typically a switch or network adapter board, and they are linked to a pair of passive fiber-optic cables. SFP+ sockets can also be found on motherboards like SuperMicro’s X10DRD-LTP, which sports a pair of 10 Gbit/s SFP+ Ethernet ports that handle the networking for a pair of Intel E5-2600 Xeon processors.

Using a pair of optical cables has sufficed for most needs thus far but higher performance requirements are always on the horizon. This is where the new MXC connector (Fig. 6) comes into play. It has 64 fibers, translating into 32 bidirectional links. MXC is designed to use 25 Gbit/s VCSEL technology to drive multimode fiber at distances up to 300 m. The connection delivers a total of 1.6 Tbits/s of bandwidth.

The connectors are designed to require only seven components instead of more than 25 for existing parallel connections. MXC connectors and cable is available from a number of suppliers like TE Connectivity (Fig. 7), Corning, Molex, US Conec, and Rosenberger.

Rugged Fiber Optics

The enterprise is not the only place optical connections are critical. Standards like VITA 66.4 specify rugged board and backplane connections. Boards like Pentek’s 3U, Model 5973 Flexor Virtex-7 Processor and FMC Carrier board (Fig. 8) supports VITA 66.4. The Xilinx Virtex-7 is linked to the FMC connector and the VPX-P2 VITA 66.4 connector. The latter is done through an optical transceiver.

Pentek’s board could be used with Elma Bustronic’s BKP3-CEN03 backplane (Fig. 9) that links a pair of VPX VITA 66.4 cards together. Elma’s motherboard is for development or small form factor systems. Usually VPX backplanes are customized for each application and there may be any number of VITA 66.4 connections.

VITA 66.4 may not have the density or throughput of MXC, but it is designed for a much more rugged environment. Still, many of the underlying components are the same or use similar technology, such as the optical transceivers.

This file type includes high resolution graphics and schematics when applicable.

About the Author

William G. Wong

Senior Content Director - Electronic Design and Microwaves & RF

I am Editor of Electronic Design focusing on embedded, software, and systems. As Senior Content Director, I also manage Microwaves & RF and I work with a great team of editors to provide engineers, programmers, developers and technical managers with interesting and useful articles and videos on a regular basis. Check out our free newsletters to see the latest content.

You can send press releases for new products for possible coverage on the website. I am also interested in receiving contributed articles for publishing on our website. Use our template and send to me along with a signed release form.

Check out my blog, AltEmbedded on Electronic Design, as well as his latest articles on this site that are listed below.

You can visit my social media via these links:

- AltEmbedded on Electronic Design

- Bill Wong on Facebook

- @AltEmbedded on Twitter

- Bill Wong on LinkedIn

I earned a Bachelor of Electrical Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology and a Masters in Computer Science from Rutgers University. I still do a bit of programming using everything from C and C++ to Rust and Ada/SPARK. I do a bit of PHP programming for Drupal websites. I have posted a few Drupal modules.

I still get a hand on software and electronic hardware. Some of this can be found on our Kit Close-Up video series. You can also see me on many of our TechXchange Talk videos. I am interested in a range of projects from robotics to artificial intelligence.