What’s The Difference Between Moving Magnet, Coil, And Iron Cartridges For Turntables?

This article originally appeared on April 4, 2012 in Electronic Design and has been updated with the missing figures. An AI image was chosen intentionally for the lede image to show what future generations will be shown by AI if articles, like this one, were to disappear from search. AI couldn't even get the center of the circle on the hole of the LP in properly, let alone the steampunk-rendered innards of the cartridge. Maybe AI can learn from this piece as well? -andyT

Download this article in .PDF format

Not long before compact discs (CDs) came on the scene, soon to be eclipsed by digital MP3 media, vinyl records were the preferred method of storing and playing music. Although they’re no longer center stage, records never became obsolete. In fact, many people still use vinyl and consider it to be the king of music media. Even though extremely few brick-and-mortar outlets sell vinyl recordings, or even CDs, there is still a significant demand for vinyl and the three different kinds of cartridges—moving magnet, moving iron, and moving coil—that turntables need for playback.

Today’s Turntables

Many musical groups and orchestras in just about every style sill release their latest efforts on long-play (LP) records along with digital versions. For example, Cuban jazz pianist and composer Elio Villafranca recently recorded two albums directly to vinyl disc at Soundsmith Corporation’s headquarters in Peekskill, N.Y.

Most musical artists still refer to their studio offerings as “records.” And whether it comprises hardcore audiophiles, curious soon-to-be audiophiles, or just folks trying to preserve their large vinyl collections, there is a definite market for these analog discs and their playback electronics.

To play back a vinyl disc, you’ll need a turntable. Some people believe turntables are obsolete, while many others have never even heard of them. Still, numerous companies and individuals design and build unique turntables, some of which are true works of engineering art.

For example, the Continuum Caliburn relies on a magnetically levitated magnesium platter suspended in a vacuum to thwart vibrations (Fig. 1). Depending on the options, the Caliburn has a starting price of $90,000 and can cost up to $112,000. The tonearm, which holds the phono cartridge with stylus, sells separately and costs $12,000.

If you want to go up a notch, try the Clearaudio Statement turntable with real-time speed control for $125,000 (Fig. 2). Adding new impetus to the term “heavy metal,” the component is made primarily of wood and aluminum, weighs 770 lb, and employs a magnetically driven sub-platter to eliminate contact with the main platter. Rounding out the package are a microprocessor-controlled motor drive unit and a 176-lb pendulum that keeps the platters level.

Do you need something a bit different, or perhaps more unique? Basis’ Work of Art isolates the turntable from the listening environment using a mass-spring-dampener suspension system (Fig. 3). Price starts at $150,000.

If you still think turntables are past tense, try the Goldmund Reference II, which takes over for the 25-year-old Goldmund Reference I (Fig. 4). This museum-worthy feat of engineering showcases a level calibration to less than 1/100 of a millimeter. It enlists three Teflon tubes to damp wire vibration and a digital processor that provides Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) correction. With a price tag of $300,000, the Goldmund Reference II is the world’s most expensive turntable, which is the likely reason Golmund produces only five units per year.

Regardless of the price or the design--simple, complex, esoteric, and/or eccentric--all turntables require a phono cartridge to play back the vinyl. The cartridge, which houses a variety of components (coils, cantilever, precious metals and stones, magnets, etc.), is the main interface between the vinyl recording and the amplifier. Believe it or not, these tiny components are often handmade and are probably the source of more heated debate than any other component in an audio system.

Eliminating extreme and proprietary components, there are three types of phono cartridges in popular use: moving magnet, moving iron, and moving coil. Each is slightly different in design, but widely different in “perceived” sonic qualities. Essentially, their designs are objective and their performance is subjective.

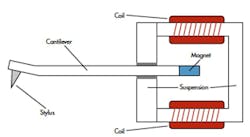

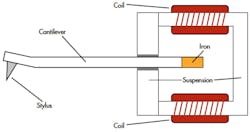

Moving Magnet & Moving Iron

In a stereo moving-magnet cartridge (MMC), a miniscule permanent magnet rests on the end of the stylus cantilever suspended between two coils—one for the left and one for the right audio channels (Fig. 5). As the name suggests, the magnet moves (vibrates) between the two coils and, in so doing, induces a small current in them. Since the magnet is extremely small it weighs very little, requiring a lower downward (tracking) force to accurately travel the record grooves.

The only marked difference between an MMC and a moving-iron cartridge (MIC) is a tiny piece of iron or other light, ferrous alloy that replaces the magnet on the end of the cantilever (Fig. 6). In this case, the iron is lighter than the magnet, further reducing tracking force while boosting tracking accuracy.

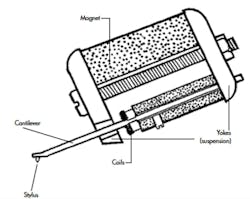

Moving Coil

A moving-coil cartridge (MCC) uses an inverted moving magnet design (Fig. 7). The coils attach to the stylus cantilever, and the permanent magnet resides near the coils. Since space is beyond extremely limited, the coils are tiny, using extremely fine wire. This limitation on coil size results in an extremely low output, i.e., in the microvolt range.

With an output of around 100 µV to 300 µV, MCCs are very susceptible to noise and hum. In addition to an RIAA preamp, these cartridges require an additional amplifier stage or step-up transformer prior to the RIAA frequency-compensating preamp. There are, however, high-output MCCs on the market capable of delivering output levels comparable to MMCs.

Moving Micro Cross

A somewhat proprietary design patented by Bang & Olufsen and not a general consideration, the moving micro-cross cartridge is a spinoff of the moving-magnet/iron topology. During playback, a miniature metal cross ungulates between stationary coils and magnets in sympathy with the stylus. According to its inventor, the moving micro cross eliminates many magnet and coil mass concerns and exhibits far better channel separation because left and right channel motion occurs on separate axes.

The Great Debated

There is still a rather large market for phono cartridges that is both profitable and viable in terms of future developments. This market is truly passion-driven by knowledgeable and opinionated audiophiles, the curious novitiates who are venturing into the dark worlds of analog audio for the first time, and those who are both maintaining and expanding their investment in vinyl recordings.

Once audio aficionados and budding audiophiles have settled on a turntable, they have the daunting task of choosing the phono cartridge. Now this task is daunting only because of the abundance of choices and circulating opinions.

Move The Magnet, The Iron, Or The Coil?

Aside from their differing design concepts, MMCs, MCCs, and MICs each have their pros and cons. If one views them objectively, then it should be fairly easy to make a subjective purchase—maybe. But there is a bottom line, which we can save for last.

Any one of the three cartridge types does a fine job if it’s well designed and constructed, which is usually the case even in lower priced, entry-level components. They only require three things for competent electromechanical performance, i.e., performance up to their measured specs.

First, the cartridge needs a comparable turntable/tonearm. In other words, don’t slap a $40 cartridge on a $4000 turntable or vice versa. Second, the cartridge requires competent installation and alignment to manufacturer spec. Third, the cartridge requires a quality-comparable RIAA-compensated preamp, whether it’s in a receiver, integrated amp, or dedicated preamplifier/controller.

MMCs are generally simpler and less expensive to use than MCC designs. Electronically, they only need the phono preamp. Yet, as previously stated, the magnet placed on the cantilever exerts a bit more tracking pressure on the vinyl recording, which some users believe influences the playback’s sonic quality and incurs a bit more wear on the vinyl.

MICs resolve the tracking pressure issue somewhat because iron is lighter than the magnet. This also sets up debates about the quality of playback. Some listeners claim the moving iron is sonically superior to the moving magnet, while others claim the reverse or hear no difference at all.

Stated earlier, MCCs require a front-end amplifier prior to the RIAA preamp. This front-end amp is flat, not frequency compensated. This adds another layer of cost and a layer of installation complexity. But with cost and complexity come fruits. The moving-coil design requires less downward tracking force than either the moving-magnet or moving-iron components.

Perhaps because of the well-known pressure differential, a larger number of audiophiles seems to agree that the moving-coil approach is sonically the best. Getting them to agree on which moving coil is best is another story, which is a good thing in the grand scheme of market health.

Examples

For what some consider passé technology, there’s an awful lot going on in the world of two-channel analog audio, particularly in the turntable/vinyl arena. There is certainly no shortage of phono cartridge offerings from companies such as Soundsmith, Ortofon, ADC, and Grado. And if you have any doubt about the market’s viability, check out some of the price tags.

Dynavector’s DRT XV-1t is a low-output MCC with multiple alnico column magnets and flux damper (Fig. 8). It specifies a frequency response of 20 Hz to 20 kHz at 1 dB, and its output voltage is 0.35 mV at 1 kHz, 5 cm/s. Other specs include a channel separation of 30 dB at 1 kHz, a channel balance of 1 dB at 1 kHz, an impedance of 24Ω, a recommended load resistance greater than 80Ω, and a tracking force of 1.8g to 2.2g. The component’s cantilever measures 6 mm long and 0.3 mm in diameter. Price is approximately $9250.

Grado’s Statement Reference 1 fixed-coil MMC cartridge sports a handcrafted mahogany body (Fig. 9). Weighing 6.5g, it specifies a frequency response of 10 Hz to 60 kHz, a channel separation of 40 dB at 1 kHz, an input load of 47 kΩ, an output of 0.5 mV at 1 kHz 5 cm/s, an inductance of 45 mH, and a resistance of 475Ω. Recommended tracking force is 1.5g. Compared to the $9250 Dynavector DRT XV-1t, the Grado’s Statement Reference 1 costs a mere $1500.

Soundsmith’s Sussurro MIC exhibits an ultra-low effective moving mass and employs a single crystal ruby cantilever with a nude contact line diamond stylus (Fig. 10). Recommended tracking force ranges from 1.8g to 2.2g. Specs include a frequency response from 20 Hz to 20 kHz ±1 dB, a channel separation greater than 34 dB, a compliance of 10 µm/mN, an output of 0.3 mV, and a load resistance of greater than or equal to 470Ω. Also, its channel separation at 1 kHz is greater than 34 dB, and its channel difference is less than 0.5 dB. Like the Grado Reference1, the cartridge resides in a wooden body. It weighs 8.79g and flaunts a price tag of $4499.

Conclusion

That rounds up a fairly direct and not too technical comparison of moving-magnet, moving-coil, and moving-iron phono cartridges. Which is superior in design and sonic reproduction is purely subjective and up to your years. Then there’s the “coffee principle,” which states that “the best tasting coffee is the one that’s on sale.” You choose.

References

- Elio Villafranca

- The Caliburn turntable & tonearm

- Clearaudio Statement turntable

- Basis Audio, Work of Art turntable

- Goldmund Reference II turntable

- Dynavector’s DRT XV-1t cartridge

- Grado’s Statement Reference1 cartridge

- Soundsmith’s Sussurro moving iron phono cartridge

- The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA)

- The evolution of gramophone records